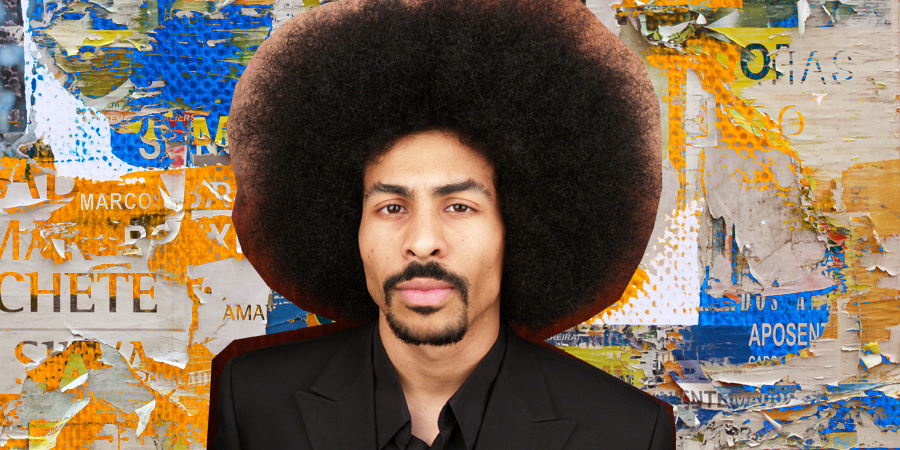

In this episode, Kimberly García talks to poet, actor, and humanitarian Sean Hill, who was born and raised in Los Angeles, and whose parents are from Bogotá, Colombia, and Harlem in New York City.

By KIMBERLY GARCÍA

EL NUEVO SOL

Kimberly García: Welcome to Radio Nepantla, a podcast from El Nuevo Sol. The multimedia site for the Spanish language journalism program at California State University at Northridge. My name is Kimberly García. The title of this series is Afro Latinx, we want to tell here diverse stories of Afro Latinx, Black Latinx and Afro Latin American identity. According to the Pew Hispanic center, one out of every four Latinos in the nation identifies as Afro Latinx. This is the same proportion of Afro Latin Americans in that region. We decided to use the term Afro Latin x with x to be inclusive of non-binary people. The umbrella term Black Latinx refers to biracial people with one African American and one not next parent, the umbrella term Afro Latin American refers to people of African ancestry in Latin America. In this episode, I interviewed Sean Hill, a poet, actor, and humanitarian.

Sean Hill: I grew up in L.A.—I was born in L.A., raised most of my life in Inglewood, California. I was born to a Colombian mother from Bogota, Colombia. And my dad was originally from Harlem, New York, with family that traces back to St. Kitts and the Caribbean.

Kimberly García: Hill rejoiced in both cultures, he spent time with his Colombian side of the family, as well as with his African-American side, he equally enjoyed the food and music, both cultures has to offer.

Sean Hill: I had mainly Black and Latin neighbors, for sure, mostly, and, that kind of neighborhood feeling of just everyone looking out for each other. Like, to this day, even my neighbors still, you know, make sure that, if we parked on the wrong side of the block, they look out for us. So, it’s been really nice to have that inclusivity feeling there—I’d say, even during the time of, gosh, when Rodney King officers got acquitted back in the ’90s. And things got a little like, you know, just a little crazy everywhere. Um, I still remember a lot of, a lot, of solidarity—a lot of people like understanding the plight that was going on and, and there was more discussions of race in police brutality, even back then. And, and I remember, yeah, I remember coming together with a lot of people. And, gosh, I’m, you know, I’m also living in a neighborhood where, you know, every now and again, we’ll hear about a drive by every now and again. Or, you know, someone that got, you know, their home got broken into, but then I hear that’s pretty commonplace—now, in a lot of areas in L.A, I think. I think growing up life for me was as diverse as I made it to be, even though I wasn’t aware of, of race or culture in a way, you know? Like a lot of kids were growing up. At a certain point, I think I, I did notice the factions, the Black kids were always by the cafeteria or the the lag kids were right on the quad on the grass area just hanging out there. I was always the kid like that could travel between all these different worlds. And then I still wanted to hang out and play basketball the most, though, you know? I was just always on the basketball court. And just having fun with the guys over there who (were) playing ball. I was on the high school swim team. And even then, I was probably one of like three or four Black students that were on the high school swim team at the time I went to Palisades High School, right? And that was a Charter High School. You know, my parents wanted to make sure that I had a good education and also less, you know—nothing bad to happen. So even then, it was like, one or two school shootings that happened there. And fights broke out every now and again. And I did meet a racist teacher there. So even then, even then, you know, we’re like, just doing our best there.

Kimberly García: Despite his inclusive environment, Hill faced microaggressions from others simply for being half African-American.

Sean Hill: Yeah, it’s, it’s moments sometimes where I don’t know, if they’re connected to race or not, or if they’re connected to just someone’s, um, like, stubbornness, or, or their own kind of privilege that they have, right? And I mean that in the sense of when, you know, if I get interrupted or talked over, right, things like that, that happened…

You know, and that kind of dismissal sometimes would happen. When I would speak with certain White people of certain ages or… I remember saying to someone, like, you know, you know I’m like 37 years old, right? And letting them know, like I’ve had experience in my life—that I may sound young or look young to some people but I’ve had a wealth of experience in this world.

And I remember talking about race with one friend of mine, one musician friend of mine. And he was like, “oh… wait, how old are you again? Oh, okay. Yeah, sorry about that.” And I was like, “oh, so now you’re gonna respect my opinions? Okay, got it. Got it. Okay, good to know.” So some people are even ageist without being aware of it. Right? And, it’s hard to separate those kind of things—in the middle of an argument or the middle of a debate. Um, you know, the kind of moments where all the toughest microaggressions, I think, are—are when someone’s asked me a question about my culture, or about, you know, even why some Black people use the N-word, for example.

And then I’m answering this man, and he was from another country who’s foreign, he was trying to get a grasp of it. And then after I explained it, to him—the full the full scope of it—and how far back it goes, the kind of freedom of it now to even have that, that word, to be able to own it, and all that kind of stuff. Not everyone uses it all. Like I went into the whole story about the N-word. And he kind of still kept persisting on why he thinks Black people love to use it, or why he thinks it’s so used by everyone—and then almost getting to that place where he kind of wanted to use it, you know? He would talk about that, like, “so I use it in this song” or whatever. “Is that—that’s okay, come on, right? Come on, come on, it has to be.” And that kind of—those kind of microaggressions that, that start off frustrating, or comical, sometimes even—But then when you realize that they’re not listening to you or taking you in or respecting your, even your entire experience that you just shared with them so intimately—but it’s still not accepted it. That’s where the microaggressions start building up, you know, and they start hurting… I don’t know.

…I don’t know if I would consider it a microaggression, I guess, but there’s times where I’d say, like even a run in with an officer—they said a macro description, and I had to be put in the back of a police car for maybe ten minutes or so. And they went through my car, they went through my van, that I was using—my mom’s van, and just went through it all. I don’t remember if they asked to go through it actually, or if that was an actual illegal search or not. Or if I did say, “okay, you can look through it.” To be honest, I don’t remember. But I remember at the end of it… a light-skinned Black-looking officer that said, “sorry about that Brother.” You know, these things happened some time and he was trying to be consoling at the end of it. But then, you know, it didn’t feel good to not be approached with that same consideration—or that same… “brother” comment at the beginning of it—You know, that “guilty before proven innocent,” never feels good. So… I mean, it’s kind of bigger than a microaggression. Right? But it was still, it was one of those smaller things that I can pick up on and notice after the fact, you know?… I could probably list a few more if I really think think hard about it.

Kimberly García: It was in grade school, where Hill first discovered what it meant to be Afro-Latino, and faced stereotypes about his hair for the first time.

Sean Hill: Yeah, there was like those little pokes and jabs at for sure in elementary school—about my hair. Yeah, about my hair. Like I had a bigger I—I had an afro also when I was in elementary school—it wasn’t anywhere this size, by the way. And I remember being made fun of for that. And then there were times where, like, yeah, I could get praised for it in the same day. Sometimes, you know, people would like it—some people wouldn’t.

Kimberly García: Even in safe spaces, negative comments were still made about Hill’s hair.

Sean Hill: I think, yeah, whenever the the family does it, it’s the—it’s the hardest. So to this day, mi abuelita would like not like my hair. She just doesn’t. She doesn’t understand it. She’s like, “why is it—why is it so big? Why do you—okay, let’s just do that.” And it’s really sweet. I’ll make fun of a joke. I think of a joke to make fun of back and you know, we laugh about it. But thankfully, it doesn’t feel as personal when she makes fun of like my uncle’s like hair or something or his beard and she just goes in—my abuelita. Yeah, she’s hardcore. She’s just, she’ll make fun of you—no matter what you are, no matter what you look like. Yeah, I think I could say that for sure.

Kimberly García: Hill later learn the significance of his hair and began to embrace it.

Sean Hill: I don’t think I fully embraced my hair until college right? Because I didn’t. I didn’t know the history behind—I didn’t know the full context of what my afro meant to so many people. And, and growing up, I even I had a bald head actually for most of my high school life. Because I was on the swim team, like I said, so it just made sense to be bald and are like, “yeah, I’m just being aerodynamic,” you know? And it was pretty great. And even now, again, every now and again, I still kind of miss a good breeze on my head, you know, just seems so magical that breeze. I was in front of a Barnes and Noble, I was parked in the car. And this, this, this Black woman came up to me on a bicycle, like she was or she was getting her bicycle or something. And she she approached me and said, “you know, young man, I have to ask, like, what made you decide to grow your hair out like that?” And I told her the same thing I told you—”for a play,” you know, I’m in college, right? And she says, “well, I just, I just want to make sure you know that it’s very special, that you have your hair out like that. And it means a lot to a lot of people. So I just wanted to appreciate you for that.” And I was like, “oh, okay.” I kind of didn’t know what to do with that, you know, and, and ever since I kept growing it out, I would get more responses like that.

Kimberly García: Hill recalls facing an identity crisis, while trying to balance his Colombian background, as well as his African American culture.

Sean Hill: You know, my mom would speak Spanish every now and again, but not often. And, and the thing is also my brother, the first five years that he was born, they were living in New York with my, with my grandmother, right? And she spoke only Spanish. And even to this day, she speaks mostly only Spanish with maybe English, you know, she could understand basic English stuff. So he grew up speaking Spanish. And, and I kept trying to learn Spanish in high school and took two—three years of high school Spanish, another year of college Spanish. I still plan on going to Colombia and like living there for a little bit to even immerse myself and get Spanish, you know, because I really want to get that under my belt for sure. And, and be able to speak to my grandmother, hopefully, you know, sooner than later. And have fuller conversations with her, but um, yeah, it was mostly English at my home, for sure. Because that was definitely part of that phase I told you about earlier when I was in high school, right? And I went through that specifically with that feeling of lack with the language, you know… So many people at the time spoke Spanish and, you know, had this, you know, beautiful secret club, like… code language that they could use. And, and I have the genetics, but I don’t have the language, you know, and that would throw me for a loop for a while for a number of years, I would feel bad about that, or not feel included on certain things. Or, you know, I’d have to ask my mom all the time. “Okay, what did they say? What do they say? What did they say? What did they say?” …That reliance—it was tough to deal with it was—it made me feel kind of either weaker, or not as… there’s some shame in there for sure. Like, how come I can’t pick up this language quicker? How come it’s not sticking? You know, I’d be harder on myself. I’d be super proud when I did get a couple sentences down. And I’d be like, “yeah, you know, the dude is scared that you know.” And I started picking up like little words that I could use, and it was more than just like a spoiler, right? And, you know, I could conjugate a verb, you know, and it was, it was great, it was great. And then, you know, then I get on myself, if I’m not practicing enough, you know, from my man, I feel like I’m letting people down or something weird in my head, you know, and, and I get it, I get it now, because there is a lot of pride in language, there’s a lot of pride there. And thankfully, I’ve met so many other people that were in similar situations like me, where their parents were just working all the time. They, they, they didn’t have time to speak Spanish at home, or, you know, they couldn’t take those, you know, elective courses, because they had to work and, you know, make money for their family and help out in that way, right? So, you know, I’ve heard all those kind of stories. And it gave me a lot more patience, it gave me a lot more self love for myself, you know?… Being part of a culture doesn’t mean, you have to check off all these boxes, you know?

Kimberly García: For Hill, the connection to his culture meant more than just the language.

Sean Hill: And every time I went to, you know, even a march for like the, for the DACA March, or if I wanted to, you know, closing down the ICE detention camps, like, I still knew I was part of the cause, like, I still know, I was in solidarity, you know, and I still felt that kind of that kind of connection that that mattered more to me, than if we’re connecting through language, you know, and it not to completely downplay it, of course, because, you know, I could say if I don’t like the similar sports team as you, that doesn’t mean we can’t talk right like we just, I like tennis, you like baseball, right, whatever. And we’d still can still enjoy each other’s company. enjoy each other’s time and hang out and still bond, right? So I started trying to kind of like look at language in that way, and see all the different ways that I could bond with someone besides that, and, and it was beautiful. It was amazing. Um, it really opened up my heart and opened up my mind a lot more

Kimberly García: Hill is an amazing poet who used his art form as an outlet to get in touch with his most authentic self.

Sean Hill: If I did not have poetry. By my side, ever since I was in middle school, I started writing, I would be a drastically different person, for sure. Unless, I mean, unless I had some other outlet that was equally infinite. As I think poetry is, I don’t know, I don’t know, I would be a lot more heartbreak, I’d be a lot more fractured, I’d be a lot more just misunderstood. Probably I’d, I’d have to hold in so much more probably. So with poetry for me. I mean, I still remember the day when I had my first breakup. And not my first breakup, it was my second breakup, it was like my first real girlfriend really, like I knew what a girlfriend was, you know, and I wasn’t afraid to hold her hand, you know, it was like a real actual relationship, right. And I remember getting to a place where I was still really messed up about and crying about it and messed up and, and I remember just, I started to write, I started to just write, and just see where it took me. And I kid you not three, four or five pages in. As soon as I wrote that last line, I felt this clarity, I felt this, this positive emptiness. Like I was clear, like, I was like, free of that pain, you know, I felt like I understood that relationship better. And what happened and why went wrong. After I wrote all that out. It I almost saw poetry then as as a type of blueprint for the human mind, for the human heart, that we could, we could write these, this kind of map or this kind of trail, to figure out why we’re feeling what we’re feeling, why we’re going through what we’re going through, and then we can look at it again, and make sense of who we are and make sense of everything that happened, you know, um, you know, that kind of self reflection, there’s, there’s been nothing like it to me in the world that combines critical thinking, and, and critical emotional intelligence, and then makes your imagination better every time you use it. You know, it’s, it’s such a special art form to me,

Kimberly García: In the future, he’ll plans to incorporate both his Colombian culture as well as his African American culture into a family of his own,

Sean Hill: I would definitely have them learn about everyone, but at the same time, yeah, that that cultural route, or that, that kind of, I’d make sure that sacred feeling of, of their, their ancestry was there and felt as well for sure. And, and the kind of the kind of history that we have as a people as well, and the kind of things we’ve overcome, you know, it’s always special to me to say and stand out. You know, they call it a beautiful struggle, you know, in the civil rights, movement, and in, in living, it’s just in the Black community, especially I’ve heard it the most, that is to live a life of pain and oppression. And this constant kind of feeling of attack or fear sometimes, but then to still make this life as beautiful as humanly possible to that whole process is really special to me. And, I would for sure, pass it on.

Kimberly García: Thanks for listening to Radio Nepantla. La voz que traspasa fronteras. We invite you to listen to the rest of the series Afro Latinx. We will tell you stories of Afro Latinx identity. Listen to our podcast on your favorite platforms, you can also check our SoundCloud channel El Nuevo Sol or our website and mobile ElNuevoSol.net. This was a production of El Nuevo Sol, the multimedia project of the Spanish language journalism program at Cal State University Northridge. This episode was produced and edited by Kimberly García.

Sean Hill’s website: Let’s Bend Reality.

Tags: #AFLX ACTOR Afro-Colombian Afro-Latinx CSUN Kímberly García podcast Radio Nepantla Sean Hill