“From my experiences now, queer people in Central America are seen as outcasts and not as members of their society.”

By AMANDA TZOC RODRÍGUEZ

EL NUEVO SOL

To face the dilemmas of being Central American and queer contains the hardships from family, migration, and violence. A place to find safety is the mission by these communities and even those within the United States. Central American queers have to face either the US-Mexico border or the borders within the US to strive for a better life in order to be themselves.

Central American migrants of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and extensions of the LGBT community, are at higher risk in their home countries of drastic violence and persecution for who they are. Focusing on the Northern Triangle of Central America being El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras, the murder rates are up to 81.2 per 100,000 people according to the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2016. WHO also determines their murder rates of more than 10 per 100,000 people are at an epidemic level, which the Northern Triangle exceeded.

Amnesty International conducted their 2017 study, “No Safe Place,” which focuses on the interviews of Central American LGBT in the Northern Triangle and the various forms of discriminations that they endure. This being: gender-based violence, lack of protection from authorities, re-victimization, invisibility, no sensible justice, and the lack of protection when trying to cross the US-Mexican border.

There is impunity that circulates within these Central American countries that do not punish those authorities that commit crimes against LGBT people. An example of this is those 275 Honduran LGBT that had been killed in the country from 2009-2017, researched by the Honduran NGO Cattrachas , who may have been murdered by Honduran authorities.

“Terrorized at home, and abused while trying to seek sanctuary abroad, they are now some of the most vulnerable refugees in the Americas. The fact that Mexico and the USA are willing to watch on as they suffer extreme violence is, simply criminal, ”said Erika Guevara-Rosas, Americas Director at Amnesty International.

The travel towards the United States border has been treacherous in the abuses that they face upward towards the border. Prominent harassment / abuse is either through gang members, sexual exploitation, migrants or authorities within Central America and Mexico towards LGBT people. Trans women, however, are more vulnerable towards abuse in migrating.

“The ones who can’t hide their sexuality and gender, there’s a huge aggression toward them. And of them, trans women are the ones who are most heavily targeted, ”said Victor Clark-Alfaro, an immigration expert at San Diego State University, in The New York Times 2018 piece by Jose A. del Real.

Del Real interviewed Jade Quintanilla, a trans woman from El Salvador, who had reached Tijuana, Mexico but is scared to cross the border due to being transgender and the possibility of the US not granting her asylum. Yet, her journey upward towards the border came with the abuses Del Real mentioned. Quintanilla had traveled with her friends upward towards Tijuana where she had been robbed in Tapachula. She then was then sexually exploited in Veracruz while riding the Beast, a train in Mexico that migrants use to travel northbound.

“They say you can ride on top of the train. But the reality is different. We had to give our services so that they’d let us on. They were abusing us the whole way through. And if we refused, they’d threaten to push us off, ”said Quintanilla.

However, once reaching the US-Mexico border, queer Central Americans are in danger within Mexico or detention centers in the United States. For those Central American LGBT that are placed within detention centers they are faced with dicsrimination, sexual assault, and persecution for who they are . As well, they await for their asylum hearings but live in Mexico, awaiting but fearful within the area they wait. However, there are some who were able to cross that border and experience their sexual identity within the US, as well fearing that they won’t be accepted by their family here.

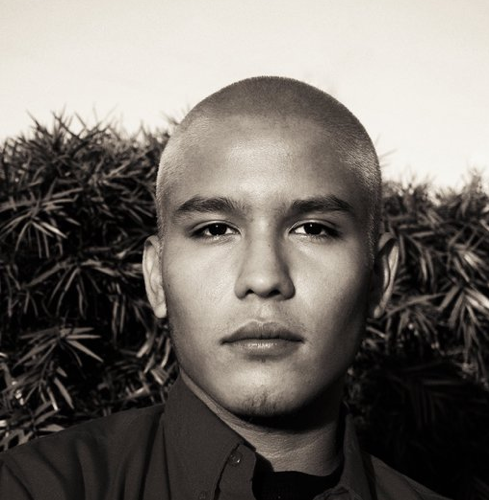

Anner Rafael Salvador, 22, had grown up till the age of nine in El Salvador before migrating toward the US He shares that he is a bisexual man and is very open with his identity; he felt his first attraction to someone of the same gender in elementary school. He had difficulty with coming out to his parents, due to religious views and wanting to be accepted for who he is.

“I decided to discuss my sexual orientation with my mom because I have always felt close to her despite her religious stand in some issues and her patriarchal and machista beliefs. I have learned that whether someone accepts me or not, I will still love myself entirely for who I am, because I know who I am and who I want to be, ”said Salvador.

He continues on explaining that he had not dealt with much homophobia in the US compared to those in El Salvador. I’ve ended on the importance of Central American LGBT stories and experiences. Especially with the migrant caravans from Central America where LGBT members have become active members in advocating for asylum, homophobia and transphobia.

“But from my experiences now, queer people in Central America are seen as outcasts and not as members of their society. . . I have a gay friend who migrated here from El Salvador about five years ago, he’s told me about many things he faced and used to see in the streets of his city Soyapango. I’ve shared with me the different kinds of violence LGBTQ + suffer and how many of them often have to hide out in order to stay alive. ”

As well, queer USborn Central Americans also face the same border with migrants with coming out and finding acceptance of who they are in their lives . However, their lives differ compared to their counterparts coming to the US as they live in an area that has more rights compared to those in Central America.

Luis Ruiz-Martinez, 19, is a US born Guatemalan who identifies as queer. I explained how his experiences were difficult understanding his own orientation and coming-out to his family. Yet, he was shocked with the reaction given to him when he was able to.

“My other relatives including my mother have been really loving and caring, I am happy I have a family I can trust. [The stereotypes were] … that they were not born this way but my grandmother told me this when I came out to her, ‘if God created you this way than so be it, God has made you a confident person and I’ m proud of you. ‘ That really shocked me because not even my father is that open and accepting of queer people. ”

In an NPR 2014 survey , “15 percent of the immigrants we surveyed declined to reveal their sexual orientation – gay or straight – while nearly all Latinos born in the US were much more open; 99 percent gave us that information. ”

US born Guatemalan, Aura Estrada, 21, had shared a different outlook in her life where she grew up in her Central American household not being exposed to any stereotypes of LGBT people and her family was able to educate themselves in the correct wording to use and respecting that everyone is different. Estrada and Salvador both explain that they have seen more acceptance within Central American’s, either in families or the younger generations.

“I haven’t heard much stories of Central American migrants LGBT +, I do believe these stories should come alight a lot more. It would mean a lot more representation within both Central Americans and the LGBT + community. I, however, do understand it’s hard to come out in general and express who you really are / identity as, I do respect the ones that do as it took a lot of courage. Like i said, I hope to one day live in a world where this is a lot more normalized than it is right now, ”expressed Estrada.

Tags: Amanda Tzoc Rodríguez asylum Central America LGBTQ