“From the time I was seven years old to about 12, it was not that good and I was really embarrassed,” said Hernández. “I always grew up with this shame because I was like I’m very proud to be Mexican and I feel very Mexican because all of my family is Mexican, like my parents are Mexican, they speak Spanish and my grandparents don’t even speak English…”

By LESLIE IGNACIO

EL NUEVO SOL

For many decades, how much Spanish a person can speak has been used to determine how Latino they are or aren’t. This brings a social pressure to anyone who is no longer a first generation born in the United States in their families.

22-year-old CSUN student, Xóchitl Hernández, has had a lifetime struggle with accepting to identify as Mexican because she has struggled with her Spanish.

Although Hernández is not the only person in the United States who feels this way, 85% of Latino parents say they speak Spanish to their children and 97% of Latino immigrant parents do too, according to the Pew Research Center’s 2015 National Survey of Latinos.

Hernández was born in the San Fernando Valley and lived in the city of San Fernando as a child, which is rich in culture and diversity in the San Fernando Valley. Spanish was her first language and basically all she knew until the age of 4 years old.

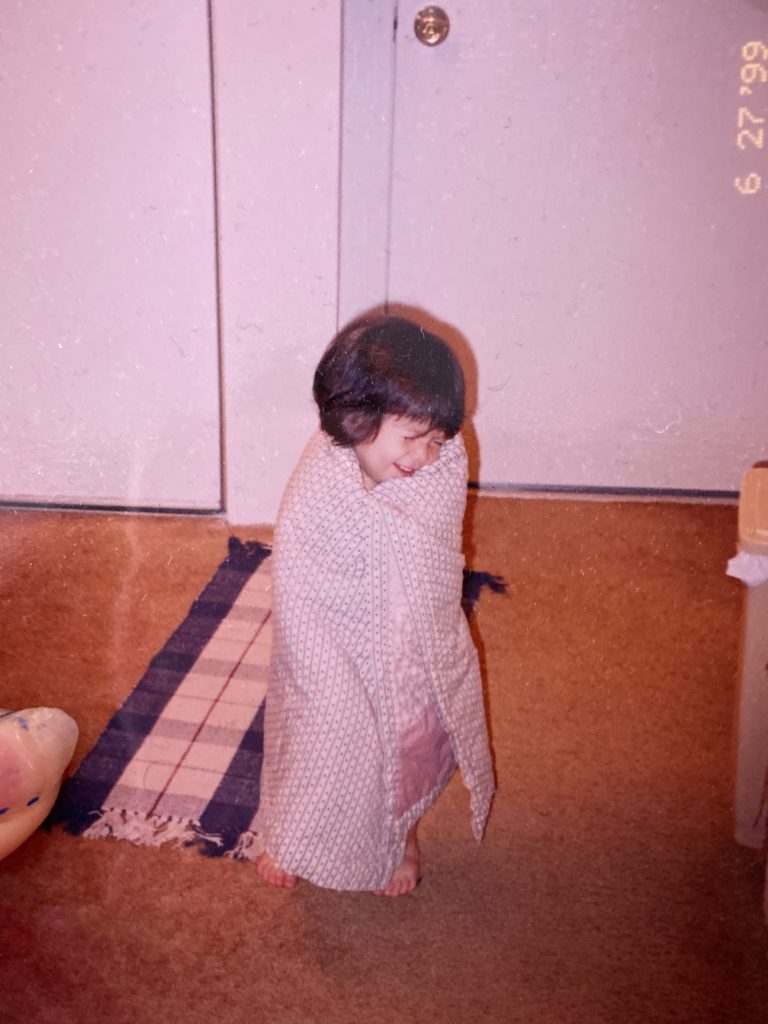

Xóchitl Hernández at 1 year old while living in the San Fernando Valley. | Picture by Xóchitl Hernández | El Nuevo Sol

“When my parents signed me up for school, my mom actually put on my application that we spoke Spanish at home and so they actually wanted to put me in ELS classes because they took it as English is my second language and that I’m going to need more help,” said Hernandez. “And so she had to go back to the school and tell them no, not that ESL classes are bad, it’s just that she said you’re misunderstanding. Just because she knows both languages doesn’t mean she shouldn’t be put in classes where she’s learning things like her peers are.”

According to the Pew Research Center, Hispanics in the United States break down into three groups when it comes to their use of language: 36% are bilingual, 25% mainly use English and 38% mainly use Spanish. Among those who speak English, 59% are bilingual.

This makes it difficult to understand why children who are bilingual early on in their lives are placed in programs like English as a second language, when they are able to fully function in a normal English class of their grade level.

As she began attending school and moved to Santa Clarita, a predominately white area, Hernández remembers her family speaking less and less Spanish. In turn, only making it more difficult for her to maintain her Spanish.

“From the time I was seven years old to about 12, it was not that good and I was really embarrassed,” said Hernández. “I always grew up with this shame because I was like I’m very proud to be Mexican and I feel very Mexican because all of my family is Mexican, like my parents are Mexican, they speak Spanish and my grandparents don’t even speak English. And I love my grandparents, but I felt like growing up especially during that time, I honestly felt so distant from them because I felt like really afraid to talk to them because it’s like what do I say, like all I know is hola, cómo estás and then I start to freeze up. And so what else am I going stay. And you know how like old school grandparents can be like oh no hablas español, ¿por qué no hablas español?”

Yet Hernández did let her surroundings determine how much Spanish she spoke and when to do so. In high school she began taking Spanish classes and became determined to continue speaking more Spanish to have people understand that she did speak the language.

“And it was just always very beautiful for me because even though I silently struggled with that I was still always like no, whatever Spanish I know, maybe I don’t know every word, but at the same time I feel like I’m going to embrace all the words that I do know,” said Hernández.

To her, embracing her Spanish meant embracing her roots, no matter what generation she came to be in her family. Hernández has always identified herself as Mexican or Mexican American when needing to be specific, but preferably uses Xicana.

According to the Pew Research Center, 33% of these young second generation Latinos use American first, while 21% refer to themselves first by the terms Hispanic or Latino, and the plurality—41%—refer to themselves first by the country their parents left in order to settle and raise their children in this country.

“Xicana because what that means to me is I am a Mexican women who has made her life in the United States and in America, therefore because of my roots of being here”, said Hernández. “The border crossed my family because my mom, her family has been here like my great grandma, my great great grandma they’ve been here in California since it was Mexico.”

Whether someone is first generation or fifth generation, the Spanish they embrace and their bilingualism is very much a part of their lives and identities as Latinos. Being able to speak both English and Spanish, allows them to celebrate both their cultures.

Tags: Bilingualism City of San Fernando CSUN Leslie Ignacio second-generation Latino Spanish Xóchitl Hernández