With undocumented moms and dads disappearing because of deportation, their families and U.S. children who are citizens are greatly suffering.

By PENELOPE LÓPEZ

EL NUEVO SOL

It has been 10 years since California State University Northridge Psychology student Sharon Alonso, 24, has seen her father. Amongst many like her, she has stepped in as a parental figure to her 3 younger siblings, struggling to accomplish her own future dreams, while those of her family have been disrupted.

Alonso and her siblings are among the estimated 100,000 American children affected by their parental deportation between 1997 and 2007. Since then, the speed of deportations has skyrocketed during President Obama’s administration. From 2008 to 2015, almost 2.8 million people have been deported according to the U.S. Department of Immigration and Customs Enforcement, and last May 12, 2016, Reuters reported that there are plans for a new wave of immigration raids in May and June with the objective to deport more Central American children and their mothers.

Contrary to the public perception and the government claims that people deported are criminals, a New York Times investigation in 2014 showed that “two-thirds of nearly two million deportation cases involve people who had committed minor infractions, including traffic violations, or had no criminal records at all.”

And with undocumented moms and dads disappearing because of deportation, their families and U.S. children who are citizens are greatly suffering. A 2012 report by the Center for American Progress found that deportations leave many children in foster care and create large numbers of single mothers struggling to make ends meet (like Alonso’s mother). In addition, the report found, children of deported parents live in constant fear of separation, are constatnly afraid of law enforcement officers, including the police, and start to associate all immigrants with illegal status, regardless of their own status.

Ten years ago, Sharon Alonso was 14 years old, excited for her next big step in life, high school. Her middle school graduation was the highlight of this point in life and she was confused on what was happening to her family.

“It did happen almost over night,” says Alonso about the time her father was detained. “We don’t know why, we never found out and I don’t want to find out. If it was an offense he had made, he is my father no matter what, I don’t want that to change.”

With an older brother, and three younger siblings, her mother was forced to run the family as smoothly as possible without allowing her children to stress over the family change with her fathers deportation.

“I didn’t see him for a month and I began to question what happened,” Alonso says. “I remembered in his court trial he pleaded the judge for one last good bye. I didn’t know why, but it was his last good bye. His last embrace that he would ever give me. The last touch before he left.”

Two months later, her mother finally sat them down and told them what had happened. Explaining that his sudden disappearance was due to him being deported. Her mother also kept their father’s transition in Mexico a secret.

“I didn’t know how he ate, where he slept, who took him in and it’s been a thing to never ask,” she says. “He wants us to remember him how he was here, with us and not what happened to him after.”

She spent the next years raising herself and her siblings. It was hard for Alonso to not have a father to love or give her advice. The discipline and advice he had given her before was missed and needed as she battled through her teenage years.

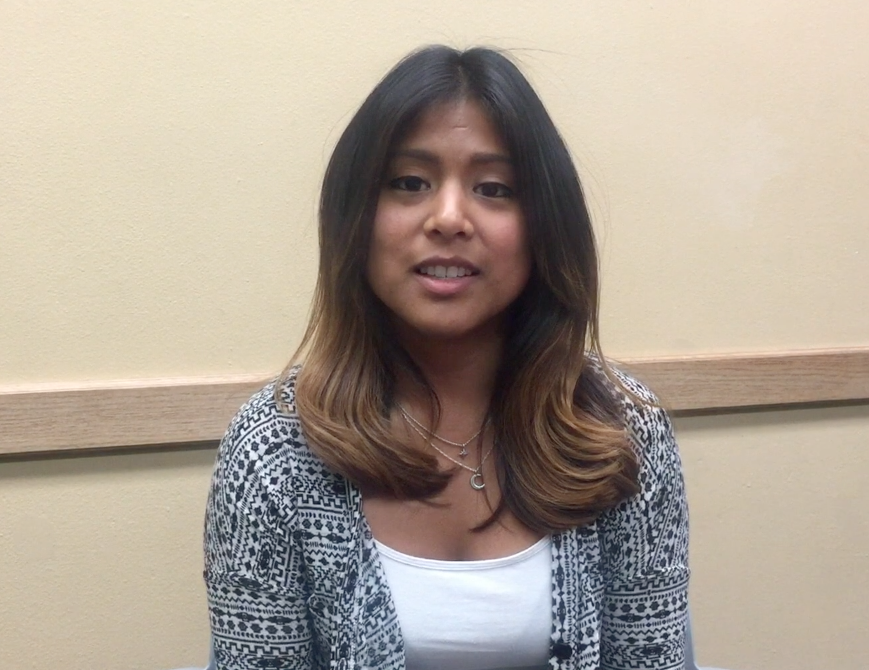

Sharon Alonso, 24, a junior psychology major at CSUN. Photo: Penelope López / El Nuevo Sol.

Alonso understood their family situation, but her siblings thought of the separation differently. To them their father had left, and the pain of leaving their family fatherless was what left them in anger and stubborn to accept the facts that had happened while they were so young.

As the eldest daughter, it was her role to take on a parental figure. Her mother worked double time, leaving Alonso to feed, care for and educate her siblings.

Her father was able to return to his hometown of the state of Puebla, Mexico, however the sudden change made everything difficult for him to adjust to his birthplace.

Given the sentence of deportation of 10 years, the family has counted the days until they would once again reunite. With costly expenses, confusing and unclear regulations and forms, the process of his return has not been as easy one.

“He was here for over 20 years. He’s slowly giving up and accepting the fact that he will never be able to come back,” says Alonso.

“My dad does have a Facebook, Instagram and it’s just not the same,” she says. “The distance makes it different. It doesn’t feel close It’s the physical appearance that’s missing. He can’t come up to me and just be like ‘Hey Mija! How was your day?’ Our communication is through media and you don’t feel that warmth.”

Many don’t understand the process of deportation or how individuals can return. Since the increase of deportation, many non-profit organizations have gathered with a passion to help those who have family separation due to an immigrant’s removal from the U.S.

Border Angels, a non-profit organization on the border town of San Diego, helps families that are in similar situations as those of Alonso. Their volunteers advocated for human rights, social justice, and humane immigration reform, while providing different ways for families to communicate.

“I met a deported man at Friendship Park (a park located at the border of Mexico and the U.S.) who sobbed as he told me about the emotional pain separation from his wife and children caused,” says Jonathan Yost, an Event Leader for Border Angels. “He was completely lost on the other side of the wall, and struggled every day. He had been in the US for years working hard in construction to provide for his family. He told me that now his life was not worth living. It woke me up to the human cost of US Immigration policy.”

It’s situations like this that has affected volunteers in this organization. There are thousands with similar stories who have been living an American lifestyle for all their lives and one day they are forced to a foreign land.

The U.S. government has a different set of regulations to handling children who’s parents are scheduled to be deported. The Alonso Family had a mother still in the U.S. after her father’s deportation, however, there are many families that unfortunately loose all adult family members and the children are left alone in the U.S.

Laura Gonzalez, a social worker for the LA County Department of Children and Family Services is an emergency response children’s social worker dedicated to the San Fernando Valley focusing on the cities surrounding Canoga Park, has come across many of these situations.

“Children do not get taken away over night. The parents are able to coordinate with us but that only happens if there are no family members to step in,” says Gonzalez.

Gonzalez explains that there is a process to separating families within the U.S. Once a parent is going to be deported, Social Workers are to handle each case step by step. First looking for any relatives that could care for the child. If the child is first generation, then they will be placed in the system, which is equivalent of foster care and group homes.

“There’s a high percentage that are in a Juvenile Detention Center,” says Gonzalez. “Those are the left over children hate to put it that way, but people don’t want these kids and they don’t have family, there is no other place to go. These are mostly the defiant kids. Sometimes there is no self-identity so they release that anger and act out in stealing and other criminal acts. They are urged to belong to something so they associate with gangs.”

A loss of identity is another issue children face. When going to Mexico they feel as if they do not belong because they are so Americanized, but in the U.S. they feel that they don’t belong because their families are in another country. Gonzalez shares that this sense of loss is what causes depression and other psychological issues amongst children, if qualified for Medicare or other services, the children are able to get help from professionals.

“ We always aim to find family. No matter how distant the relative. If family is there for the child, the child will be released”, Gonzalez says. “We don’t check if they are documented or not just as long as a family member is there the child is checked out of the system.”

As parents continue to disappear and leave American children behind, it has become a common change in life for families living in border cities and states with changing regulations. Sharon Alonso has a message to share with those who are or who have lost parents to deportation.

“Don’t let people keep stuff like that to themselves,” she says . “It’s hard for younger people to understand why their parents have left but having that conversation helps with overcoming obstacles and allows for a push for the dreams their parents wished for them to achieve.”

Tags: Border Angels Center for American Progress CSUN deportation LA County Department of Children and Family Services parental deportation Penelope López Sharon Alonso