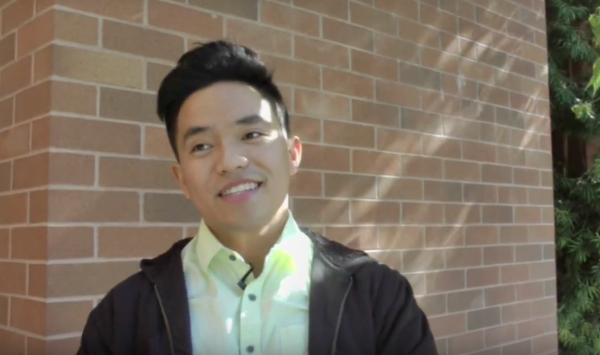

Carla Martínez, 19, Deaf Studies major at CSUN. Photo Mirna Durón / El Nuevo Sol

2015 marked the third anniversary of both Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) and the California DREAM Act. Since being implemented, both policies have provided a path for undocumented students to pursue and finance a college degree, but non-DACA recipients still struggle to gain access to higher education.

By MIRNA DURÓN

EL NUEVO SOL

In early 2011, Carla Martínez’s path to college after finishing high school looked very challenging. As an undocumented student, she had no access to jobs in the formal economy or any kind of financial aid from the state of California. Martínez was just one of thousands of undocumented students facing one of the most difficult struggles to pursue a college degree. But by the second half of that year, Martínez’s path to college started to change for the better.

In July and October of 2011, governor Jerry Brown signed into law two pieces of legislations introduced by then assemblyman Gil Cedillo: AB 130 and AB 131, known as the California DREAM Act. These bills, which went into effect in 2012 and 2013, allow undocumented students that qualify for AB 540 status to apply for and receive state financial aid and institutional scholarships.

Then, in July of 2012, president Obama announced the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA), an executive order that granted an exemption from deportation to young immigrants who had entered the country before their 16th birthday and at or before June 15, 2007. This program allows students like Martínez temporary protection from deportation (2 years) and access to work authorization, which means being able to work legally and have access to a driver’s license.

Today, Martínez is one of the almost 8,000 recipients of state financial aid under the California Dream Act for the academic year 2015–2016, and one of the 699,832 initial DACA applicants approved by the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) as of September 30, 2015. Both policies, one local and one federal, had made less difficult for students like Martínez to pursue a college degree without fear of deportation and with access to some financial aid.

“Having Deferred Action basically lets me stay here and not be afraid to live my life,” said Martínez, 19, a Deaf Studies major sophomore at California State University, Northridge (CSUN). “The work permit allows me to get access to jobs that I didn’t have before to get money, to pay for books, pay for gas, pay for rent.”

A student without a Social Security number is non-eligible to work making it difficult for her or him to have any sort of stable income. The National UnDACAmented Research Project (NURP) found that almost 60 percent of DACA recipients have obtained a new job and 45 percent have increased their earnings. Martínez is one of them.

“Right now, I am working at a retail party supply store, it’s not that much right now but it does help pay the bills,” said Martínez.

CSUN DREAM Project from El Nuevo Sol on Vimeo.

Another significant issue for undocumented students is being able to drive legally. The NURP survey found that 57 percent of DACA recipients have obtained a driver’s license. At the beginning, Martínez struggled in securing a job, but she was able to obtain her first driver’s license quickly, making her commute to school and work much easier and allowing her to take classes too early in the morning or too late at night.

“If I didn’t have a driver license I wouldn’t be able to drive to school and I have an eight o’clock class,” said Martínez. “I would have to go on the bus for two hours instead of just a 30 minute drive from L.A. to Northridge. It also helps me get to and from my job, so that also helps a lot.”

When Martínez first applied for DACA, she and her family were skeptical on how effective and helpful the program would be for her. Initial and renewal request for DACA includes a $380.00 application fee plus an additional $85.00 for biometrics. Besides, she needed help with the paperwork.

“I got a lot of help from my high school counselor and also from CHIRLA to get through the process,” said Martínez. “It was a lot of paper work too.”

NURP estimates that 93 percent of the survey respondents received assistance from community organizations, schools, private attorneys, and legal clinics within their community in filing their DACA applications.

Today, Martínez and other students at CSUN can turn to the DREAM Project Office for help to find resources on how to apply for DACA. The DREAM Project was established in 2014 by campus quality fees to help assist not only DACA students but also the entire undocumented student population of the university.

“The DREAM Project Office stands for Dreamers Resource’s Empowerment Advocacy and Mentoring—those are its main pillars.” said Darío Fernández, the DREAM Project coordinator. “Students really spoke to the need for a centralized resource space. In addition, they wanted to know that they could go there and ask all these types of questions. What is DACA? How do I qualify for financial aid for the Dream Act?”

The DREAM Project serves also a safe space for undocumented students.

“It does make me feel safer,” said Martinez, “and because of the DREAM Project, I’ve come to meet a lot of other DACA recipients so I don’t feel alone. I know that I am not alone. It is a good feeling,”

CSUN has the largest undocumented student population in the state of California in terms of DREAM Act applicants and recipients, according to figures from the California Student Aid Commission. The Los Angeles metro area, in general, has the colleges with the largest numbers of DREAM Act applicants and recipients.

“As of July 22nd, 2015 there were 1,222 California DREAM Act applications reported by the California Student Aid Commission,” said Fernández. “Of those, 731 have been awarded, so it’s a rough estimate. For fall 2015, there are 1,262 AB 540 students who also applied for the California DREAM Act here on campus.”

Also, the DREAM Project has been able to collect more information about undocumented students on campus by doing what Fernández called a “needs assessment survey.” According to this survey, 80 percent of undocumented students at CSUN have AB540 status, 76 percent are DACA beneficiaries, and 70 percent are California DREAM Act recipients.

This numbers mean that one of every five undocumented students at CSUN does not qualify for AB 540 status and one in four doesn’t qualify for or can’t afford DACA. Fernández is very conscious of this and emphasizes the need to provide support to students not only for their academic success, but also for helping them navigate a byzantine immigration and financial aid systems.

“We work really closely with students,” said Fernández. We have a peer mentoring program and we are working with students to address a lot of the needs they have as students, but also as individuals who happen to be undocumented.”

Fernández helps assist students with DACA guidelines, referring them to free community legal services such as the Coalition for a Human Immigrant Rights Los Angeles (CHIRLA), Center for Human Rights Legal Aid, and Asian Americans Advancing Justice.

Lack of enough money for the application fee for DACA could be a barrier for some students. More than 43 percent of DACA eligible non-applicants could not afford the fee, according to the Migration Policy Institute. Another 10 percent said they did not know how to apply. Furthermore, the application process does not leave room for error. If the USCIS deny a DACA application, one cannot appeal the decision or file a motion to reopen or to be reconsidered.

This is what happened to Bhernard Tila, 20, a sophomore student majoring in Public Health and Asian American Studies. Tila’s DACA application was denied after not qualifying for the program requirements. Prior to applying, Tila and his family had called USCIS asking if he was still eligible to apply although his arrival date was later than the cutoff date.

“After we turned in all the required documents,” said Tila, “we received the notification that they had denied us due to the same reason we had inquired for, such as the date.”

Tila arrived in the U.S. in December of 2007 from the Philippines, six months after the cutoff date to be eligible for DACA.

“Without DACA, I can’t work, said Tila. “I can’t represent myself, especially practicing my degree. Internships sometimes require a social security as well. I can’t have a substantial amount of income for transportation or my education. I have to resort to scholarships offered by the campus or I have to work under the table to earn as much money as I can.”

Students like Tila face serious obstacles because, although he qualifies for AB 540 status and in-state tuition, he does not have access to some university resources now granted only to DACA recipients. Tila said he would like CSUN campus to be more supportive financially, specifically by expanding work opportunities for students who don’t have DACA and cannot apply for paid internships in their field of study. But he also feels the DREAM Project is a very important step in the right direction.

“The DREAM Project is very important, especially for those non-DACA students,” said Tila. “We need a centralized space to come in, have a resource. But not only on-campus space resources but also external campus resources.”

But throughout 2015, the DREAM Project had been operating in a small space at CSUN. However, this was about to change as of the end of 2015. On November 16th, the CSUN’s University Student Union Board of Directors approved a new rental allocation for the DREAM Project, Fernández hopes to be given a bigger space by next semester where students like Martínez and Tila can come and get the assistance they need.

“I don’t know the specifics yet because it just happened but we will be having it at the USU, it is going to benefit the amount of students that can come to the office, the amount of resources and services that we can offer to students, staff, and faculty here on campus. It’s going to be a very exciting opportunity for us.”

Tags: California Dream Act CSUN DACA Darío Fernández DREAM Project undocumented students