María García has come a long way since immigrating from Mexico, but she now feels like she and her family are living the American dream.

By BLAKE WILLIAMS

EL NUEVO SOL

María García couldn’t sleep for two days.

She was about to take the United States citizenship test which left her excited, but at the same time, María was scared she would forget everything she had been studying for and working for.

María first applied to become a U.S. citizen in 1996, six years after coming to the U.S., but it wasn’t until 2021 she was finally able to take the citizenship test. 25 years of hoping to become a citizen all coming down to one test on one day.

After taking the test, María was informed she not only passed but she aced it.

“I couldn’t believe it because I was so excited,” María said. “They said you passed the test and also you can take the oath now if you want, and I said ‘Of course! I don’t want to wait for it because I’m so excited.’”

María grew up in the small town of Los Pascuales in Durango, Mexico, which today has a population of 113 people, up from 83 people in 2005, according to Pueblos America.

She didn’t have much growing up, with just two pairs of clothes, no refrigerator, TV or anything else that is considered an essential in the U.S., and a diet that consisted almost entirely of tortillas, beans, eggs and milk. Occasionally during the cold months, she would treat herself to homemade ice cream by mixing some of the milk with sugar and vanilla and letting it freeze.

Her school, Escuela Primaria Jose María Pino Suarez, had one teacher who taught all the kids from first grade through sixth grade and the children were treated better or worse based on how much money their families had.

As an adult, María lived with her family in a small house made out of adobe bricks by her husband Eliazar. It only had the main room and a kitchen that was altogether no larger than the size of their living room in an average U.S. house. There was no running water near them and the only way to get any groceries was a store that was far away.

She didn’t want that same life for her kids, Adrián and Evelyn, who were three years old and nine months old when she decided to move to the U.S. in 1990. For her, it was always about coming for a better life for her children.

“Especially where we’re from, there’s like no opportunities. There’s really nothing, nothing to do there,” Adrián said. “And my dad mentioned this, that his whole thing of coming here is he kind of foresaw what’s going on in Mexico now, like with the whole drug problem. So he didn’t want his kids to see or be near that.”

María’s family came to the U.S. before her, so she came alone. It started by taking a plane from Durango to Tijuana where she was picked up with a group by an unknown person called “La Hormiga,” which translates to “The Ant.”

La Hormiga brought them to the mountains where they had to make their journey across the harsh environment by running for around two hours and hiding in bushes and brushes when they saw patrol helicopters.

“You don’t know who drove, you don’t know who it is. It was so scary for me,” María said. “You didn’t know if that was the last day you’d be living. You can see that it is a huge walk but because we were running, you could stop somewhere and fall, and then no more. So I was scared. I don’t know how I did it.”

While life became easier in the U.S., there were still many challenges to overcome, specifically the language barrier and the lack of a social security number, but also hearing racist remarks from other people.

María said she was stopped many times by police who said she didn’t do anything wrong but wanted to check things like making sure her seat belt was on correctly while she was trying to take her kids to school.

“So when he said, ‘Okay, it’s correct, but where is your driver’s license,’ and it was hard for me because I said ‘I don’t have one,’” María said. “And he asked me why I don’t have one and I said because I don’t have a social security number. So he said to go to a parking lot and call for somebody who can drive, and that was so hard because you want to get your kids to school.”

In 2015, María got her green card, which allowed her to live and work in the U.S. permanently, along with the ability to travel and no fear of deportation.

“It was like there was no more stress in my head,” María said.

Once an immigrant receives their green card, they can apply for citizenship five years later. María applied as soon as she could, and nine months after applying she was able to become a U.S. citizen.

For her, it took 31 years since she first moved to the U.S. in 1990 to become a citizen, and this is a similar case for many other immigrants who are still trying.

As of 2019, 3% of the U.S. population are undocumented immigrants, which is 10.3 million people, a ccording to the American Immigration Council. Many of them want to become citizens but are stuck as victims in a flawed system.

With the current number of people applying for citizenship, “The length of time it will take to clear up the current backlog is approximately 76 years… In other words, a Mexican who files a petition today for his or her unmarried son or daughter can expect that person to become current in 2095,” according to the Catholic Legal Immigration Network, Inc (CLINIC).

Although the García’s applied as a family for permanent residency, once a person turns 21, they are aged out of that packet. So by the time their family had their status adjusted, Adrián and Evelyn were no longer part of their application.

They are protected under Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA), which was announced by former President Barack Obama in 2012, but it is not a permanent law so any presidential administration could try to terminate the program, as former President Donald Trump tried to do in 2020 and declined to take new applicants for the program.

Prior to his protection under DACA, Adrián said applying to college was a stressful time. His high school counselor told him he would never go to college because he lacked a social security number, which would make him ineligible for a bank account and loans that many students need to afford higher education.

“It broke my heart when he came here to cry and couldn’t stop crying,” María said. “He wanted to quit and I wanted my kids to go to school. So I told him ‘don’t cry, this is why your dad and I are working for you, because you are going. We are not asking the government for money.’”

For most kids in the U.S., they don’t need to worry about much outside of their schoolwork and playing, but Adrián and his generation always had the concern about which immigration laws were being pushed by politicians.

“If you grew up around that time, then even a lot of people my age still remember those laws, because we saw our parents were scared, and then that also makes you scared,” Adrián said. “So a lot of kids of my generation are more socially aware of things that went on when they were children because of the fear of those laws growing up.”

Adrián is part of the Walkout Generation, who the L.A. Times described as “Young adults from across Southern California who walked out of schools” in 2006 “to protest proposed immigration legislation.” He participated in the walkouts and his generation saw they were being failed by the system despite spending nearly their entire life in thecountry.

“Most of us feel like we’re an American,” Adrián said. “And in a way, we kind of feel like the system left us behind.”

Although he is protected under DACA, he needs to re-apply for it every two years, which costs

$495 and adds stress to their lives by going through the process again, which sometimes takes months to complete.

He wants to become a citizen, but it could end up taking another 20 or more years to get it if he were to wait for the normal process. The other route to citizenship is through marriage and he is getting married soon to his fiancé, Jacqueline Duong, so that will help expedite his path toward citizenship.

But there are around 640,000 DACA recipients in the U.S., according to United States Citizenship and Immigration Services, with close to 40,000 more pending cases who still need a path to citizenship. Adrián would like to see DACA made into a more permanent solution as he believes it would be a good starting point for a solution to the problem.

However, he doesn’t have much hope that it happens because of how politicized DACA and the system has become, often being used as a bargaining chip from Democrats and Republicans to gain more negotiating leverage.

In 1996, María had another son, Uriel, who became the first U.S. citizen in his immediate family because he was born in the country. Uriel said that added extra pressure to him to succeed because he was given more opportunities than his parents and siblings.

“There was some pressure felt, I feel like it’s pretty common though,” Uriel said. “A lot of my peers in school were also first citizens and their parents were immigrants. So a lot of people are able to relate with me and feeling that pressure so I know it wasn’t alone.”

His whole family is now protected under laws that would prevent that from the possibility of deportation. Even though it has been a hard path with many challenges and obstacles, they feel they are now living the American dream.

“Obviously, it’s such a huge relief, especially knowing they’ve come a long way too since they first immigrated here,” Uriel said. “Just knowing that I can keep my mom and dad here in America, my dad has his residency and my mom has her citizenship, so I know they’re gonna stay with us here and they’re not going to be leaving any time soon.”

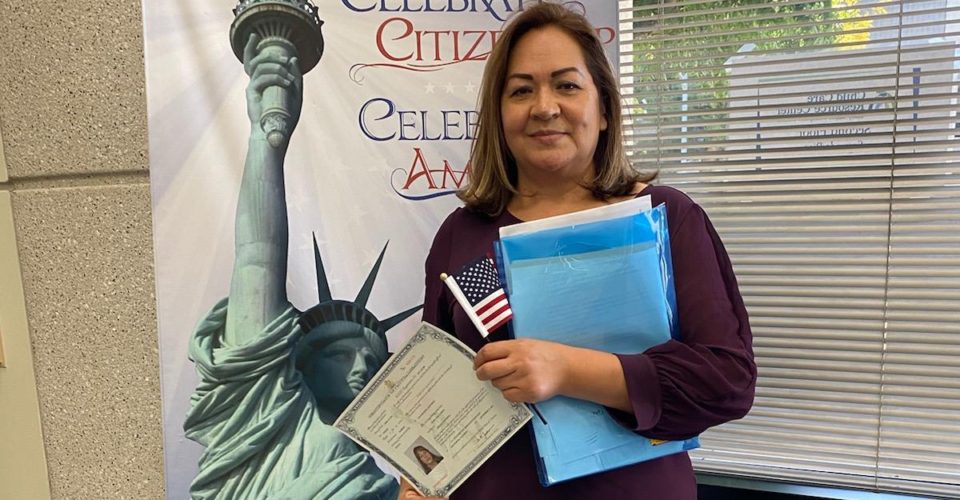

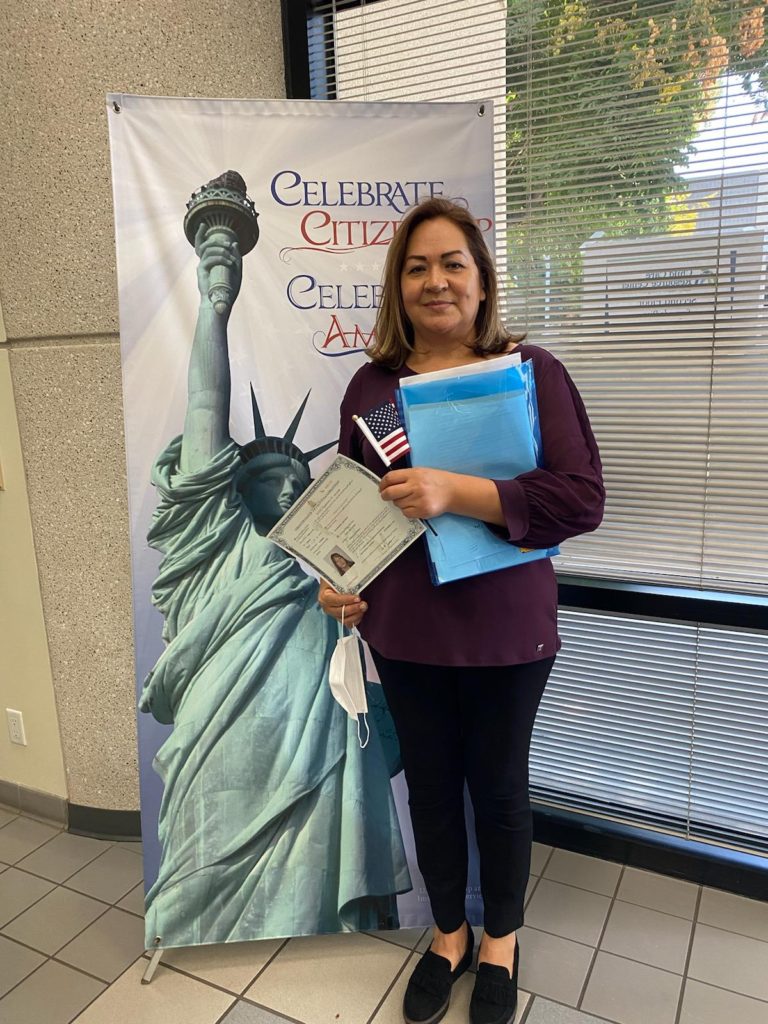

María García, a Mexican immigrant, takes a photo with an American flag and paperwork signifying she is a U.S. citizen after passing the citizenship test. Photo courtesy of María García.

Tags: citizenship DACA immigrant immigration Mexico Walkout Generation