The Mexican-American border wall stretching out to the Pacific Ocean at Friendship Park.

Photo: Blaise Scemama / El Nuevo Sol.

By BLAISE SCEMAMA

EL NUEVO SOL

We hit the road for Friendship Park, early Sunday morning in the pouring rain. Friendship Park is a half American, half Mexican, bi-national park located on the edge of San Diego and crosses over the border to Tijuana. Over the years, it has become perhaps one of the most prominent and recognizable symbols for US and Mexican relations and immigration policy, since it was erected in 1994.

Just a day before we arrived at Friendship Park, it was filled with TV crews, photographers, and reporters, clamouring to capture the unprecedented opening of the gates, which happens only once or twice a year. They call it Children’s Day and the media seems to absolutely love it.

Children’s Day is the day when Border Patrol allows 7 families, who have made a list, to hug for 3 minutes each, before the gates are closed again for another year and family members must return to the country from where they came.

Josué Aguilar, my friend and editor at The Sundial, came along for the ride and would act as my interpreter and second photographer if needs be on this expedition to the border. On the road, I mentioned to him that I was a bit apprehensive about meeting my unofficial park guide, María Teresa Fernández. Fernández is one of the founding members of an organization called Friends of Friendship Park, which advocates for the rights of immigrants and those who visit the border.

Member of Friends of Friendship Park, María Teresa Fernández, touches the pinky fingers of children through the the mesh covering of the border wall at Friendship Park.

Photo: Blaise Scemama / El Nuevo Sol

I had been communicating with Fernández via email for a week before arriving at Friendship Park but had yet to talk with her over the phone or in person. This made me a little nervous. I was afraid I wouldn’t be able to find her when I finally found my way to the park. However, when we arrived at the front gates, Fernández had just pulled up herself and we were able to start our guided tour.

Before entering Friendship Park, you must park your car outside the gates and walk 30 to 45 minutes before arriving at its entrance. On our hike, Fernández pointed out a border patrol SUV, dragging four large tires, chained to it’s hitch. She explained to me that the tires were used to smooth over the dirt so as to better find footprints of undocumented immigrants, trying to cross the border.

Border Patrol agents use tires to comb the dirt near the Mexican-American border in order to better see footprints of undocumented immigrants attempting crossing the border.

Photo: Blaise Scemama / El Nuevo Sol

As we got closer to the park, I noticed multiple surveillance stations and cameras and patrol cars going up and down a freshly constructed road that went all along the outer gates of the border. I was immediately reminded of Todd Miller’s book, “Border Patrol Nation,” in which he explains how after 9/11, Border Patrol became an agency under the umbrella of Homeland Security, and now has a bigger budget than the FBI, CIA, DEA, and all other federal law enforcements combined.

Surveillance cameras and secondary fence at the Mexican-American border at Friendship Park in San Diego.

Photo: Blaise Scemama / El Nuevo Sol

When we finally got to the front gates, we were greeted by a patrol agent by the name of Frank Alvarado. He noticed the camera in my hand and told me that I was not permitted to film without pre-authorized approval.

“There are good reporters and bad reporters,” Alvarado said.

Fernández and most of the friends of Friendship Park are well acquainted with officer Alvarado. Later, I would find out from most of the regulars at the park that although Alvarado, who is Mexican American himself, is known for strictly enforcing Border Patrol policy, he can also be somewhat flexible at times. Others told me, agent Alvarado was nothing more than a smooth talking public relations officer for Border Patrol. I got the impression that he was a little bit of both.

Border Patrol Agent Frank Alvarado oversees Friendship Park every Saturday and Sunday during park hours.

Photo: Blaise Scemama / El Nuevo Sol

When we entered the park, I noticed that despite the rusted, prison-style, metal wall which stood overbearingly in front of us, that this was actually a very beautiful place.

The wall which divides the park, stretches out into the crashing waves of the Pacific Ocean. After the rain had stopped and the clouds cleared away, the orange-brown rusted metal wall seemed to contrast, harshly against the pure blue of the sky and ocean. Again, I am reminded of Miller’s book, especially the part which describes the border wall and how it was originally constructed out of scrap metal left over from the Gulf and Vietnam Wars. The wall did have a militarized look to it.

The Mexican-American border wall at Friendship Park in San Diego, California and Tijuana, Mexico.

Photo: Blaise Scemama / El Nuevo Sol

As I looked around the park, I noticed that the wall divides more than just the park and two countries. It separates mothers from sons and daughters, brothers from sisters, husbands from wives, and US army veterans from the country they risked their lives to protect.

Friends of Friendship Park is an organization which helps assist families visit each other at the border. They recently appealed to border patrol to loosen visiting restrictions as part of their “Let them hug campaign,” which is a proposal to let families who have been separated by deportation, to hug under border patrol supervision. The park, which is only open to 25 people on the U.S. side, Saturdays and Sundays from 10 to 2pm, is separated by a 20 foot steel wall covered in rusted metal mesh, one can barely fit a pinky finger through. The Friends of Friendships Park’s appeal to let families hug was denied in July of this year.

Every Saturday and Sunday, 25 people are allowed to enter Friendship Park from 10 a.m. to 2 p.m. to visit family and friends through the mesh covering of the Mexican-American border wall.

Photo: Blaise Scemama / El Nuevo Sol

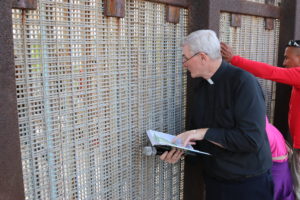

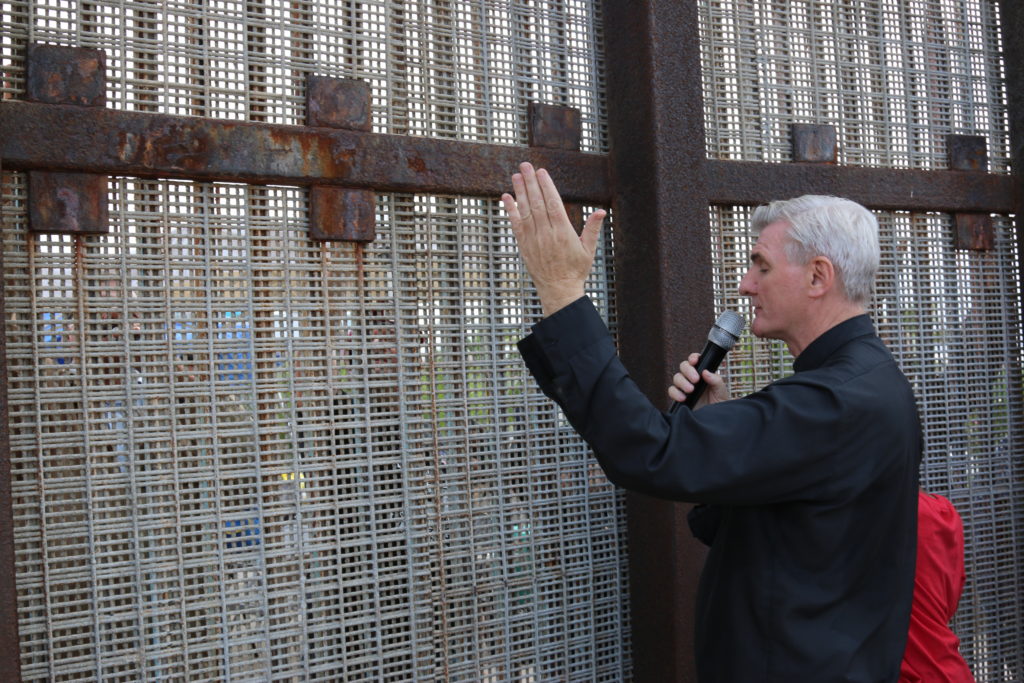

Every Sunday, two pastors who are associated with the Friends of Friendship Park, come together from both the Mexican and U.S. side to conduct a bi-national communion through the wall. The communion is conducted in both Spanish and English. The two priests read scripture and lead bilingual prayers. The priest on the U.S. side, Father Dermot Rodgers, told me that the congregation is non-denominational

“There’s enough that separates us, walls and other divisions.”Rogers said. “We’ve agreed, as religious people, to set aside our own religious denominational laws, which would prohibit some people from receiving communion.”

Father Dermot Rogers helps to conduct a binational communion which is celebrated on both the Mexican and U.S. side of the border at Friendship Park.

Photo: Blaise Scemama / El Nuevo Sol

Before the communion began, I walked around the park and spoke to anyone I could about why they were there and who they had come to see. I talked to an army veteran, who despite serving in the US army, had since been deported back to Mexico. I talked to a mother who was separated from her children six years ago due to an expired visa. I talked to a couple who started coming to Friendship Park 6 months ago, so as to speak to each other, through the fence in order to maintain their relationship, despite not being able to embrace one another.

After speaking to what seemed like almost half the people at the park, it was clear, that many of them weren’t willing to let this man-made wall stop them from maintaining their relationships with loved ones on the other side. They did what I quickly learned to do, they had conversations through the wall. In fact, one of the greatest revelations I made while visiting this binational park, divided by a massive, overbearing wall, is that whether it be a physical, religious, or political wall, one can always have conversations through it. Here are my conversations through the wall:

Much of the Mexican-American border wall was constructed out of scrap metal, left over from the Gulf and Vietnam wars.

Photo: Blaise Scemama / El Nuevo Sol

Videos

Border Patrol Agent Frank Alvarado talks about his duties at the border of San Diego and Tijuana, also know as Friendship Park. Video: Blaise Scemama / El Nuevo Sol

Robert Vivar is a deportee who comes to Friendship Park every Sunday to show support for the dreamer moms and the deported veterans. Video: Blaise Scemama / El Nuevo Sol

Yolanda Varona, leader of Dreamers’ Moms USA Tijuana talks about family separation and the goals of the organization. Video: Blaise Scemama / El Nuevo Sol

Héctor Barajas-Varela is director and founder of Deported Veterans Support House. Video: Blaise Scemama / El Nuevo Sol

Minister Dermot Rodgers talks about the Border Patrol and Friendship Park. The park is a half American, half Mexican, bi-national park located on the edge of San Diego and crosses over the border to Tijuana. Video: Blaise Scemama / El Nuevo Sol

Photo Gallery

- Only one or two days a year are children allowed to embrace relatives on the other side of the border at Friendship Park. Photo: Blaise Scemama / El Nuevo Sol

- Father Dermot Rogers helps to conduct a binational communion which is celebrated on both the Mexican and U.S. side of the border at Friendship Park. Photo: Blaise Scemama / El Nuevo Sol

- Father Dermot Rogers helps to conduct a binational communion which is celebrated on both the Mexican and U.S. side of the border at Friendship Park. The pinky kiss is considered the unofficial symbol of salutation at Friendship Park. Photo: Blaise Scemama / El Nuevo Sol

- Border Patrol Agent Frank Alvarado oversees Friendship Park every Saturday and Sunday during park hours. Photo: Blaise Scemama / El Nuevo Sol

- Members of a binational communion raise their hands in prayer on the Mexican side of the border at Friendship Park. Photo: Blaise Scemama / El Nuevo Sol

- Member of Friends of Friendship Park, María Teresa Fernández, and border patrol officer, Frank Alvarado, speak to children on the Mexican side of the border wall at Friendship Park. Photo: Blaise Scemama / El Nuevo Sol

- Member of Friends of Friendship Park, María Teresa Fernández, touches pinkies with an individual on the Mexican side of the Mexican-American border at Friendship Park. Photo: Blaise Scemama / El Nuevo Sol

- Member of Friends of Friendship Park, María Teresa Fernández, touches pinkies with an individual on the Mexican side of the Mexican-American border at Friendship Park. Photo: Blaise Scemama / El Nuevo Sol

- Only one or two days a year are children allowed to embrace relatives on the other side of the border at Friendship Park. Photo: Blaise Scemama / El Nuevo Sol

- Only one or two days a year are children allowed to embrace relatives on the other side of the border at Friendship Park. Photo: Blaise Scemama / El Nuevo Sol

- Member of Friends of Friendship Park, María Teresa Fernández, touches the pinky fingers of children through the the mesh covering of the border wall at Friendship Park. Photo: Blaise Scemama / El Nuevo Sol

- Much of the Mexican-American border wall was constructed out of scrap metal, left over from the Gulf and Vietnam wars. Photo: Blaise Scemama / El Nuevo Sol

- The Mexican-American border wall at Friendship Park. Photo: Blaise Scemama / El Nuevo Sol

- In some areas at Friendship Park, the border wall is less restrictive but only limited amount of people are allowed to enter this area at the same time. Photo: Blaise Scemama / El Nuevo Sol

- Photos of how the border at Friendship Park used to be, are placed on the floor next to accutremont of a binational-communion held at Friendship Park. Photo: Blaise Scemama / El Nuevo Sol

- Surveillance cameras are ever watchful at Friendship Park and all along the Mexican-American border. Photo: Blaise Scemama / El Nuevo Sol

The Mexican-American border wall stretching out to the Pacific Ocean at Friendship Park.

Photo: Blaise Scemama / El Nuevo Sol

Tags: Blaise Scemama border wall Friendship Park San Diego Tijuana