“I spent my days in pain because the doctor only prescribed pain medication,” Montes said. “I spent hours making lines early in the morning so I could get checked.”

Alessandro Nagrete sitting next to his mother, Irma Montoya. He’s translating from the Spanish language into the English language, his mother’s experience as an undocumented and ill women. Photo: Alex Corey/El Nuevo Sol

By DAYANIS LOREY

EL NUEVO SOL

Irma, at only 52 years of age, had to experience a hip replacement. For more than eight years, she has experienced health problems. She now depends economically on her eldest son because she is no longer able to work.

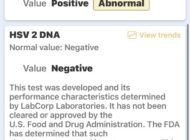

Irma is an undocumented woman who needs health care. She has been in the U.S. for over 28 years. She had to wait three years to get her hip replaced due to her immigration status. After her hip was replaced, she was prescribed with cortisone but she started gaining weight. Recovering from surgery also made it difficult for her to exercise.

She was later diagnosed with diabetes type 2 and arthritis, a condition that wakes her up every morning with a great deal of pain. Up to now, the only option she has to ease the pain is to buy over the counter pain killers. Irma is a patient at the White Memorial Medical Center, but booking an appointment with a doctor or a specialist can take weeks or even months.

Irma is among an estimated 1 million undocumented immigrants in California who cannot qualify for a health care plan due to their immigration status. The Affordable Care Act (ACA) excludes undocumented people. These are children, mothers, fathers, students, and seniors of different nationalities from all over the world according to the 2013 study, Undocumented and Uninsured, by the UCLA Center for Health Policy Research and funded by The CommonWealth Fund. These undocumented immigrants have the highest rates of being uninsured and make up 51 percent among those people who remain without health care, the study says.

The study also says that 69 percent of young immigrants lack health insurance, even though 71 percent need access to a doctor. More than half had not seen a doctor in more than a year.

To address this problem, Democratic State Senator Ricardo Lara introduced the Health for All Act. It’s intended to create an opportunity for residents who don’t qualify for the ACA, including undocumented residents.

Democratic State Senator Ricardo Lara, talking on how undocumented and uninsured residents could benefit from legislation #Health4all. Alex Corey/El Nuevo Sol

Lara is the son of Mexican immigrants, and said he grew up understanding how thousands of people, including those that are undocumented, lacked health care in California.

At a conference in early September organized by New America Media, and attended by ethnic media reporters, Lara said that any human should have the privilege and the right to have a healthy life and an affordable health plan.

The latest Field Poll, an independent and non-partisan survey of public opinion, said that two out of three California voters thought the state was successful in implementing the ACA. Another survey funded by the California Wellness Foundation revealed that the ACA is registering historic levels of support in California.

This increased support for the ACA, also known as Obamacare, could indicate a willingness among California voters to support Sen. Lara’s legislation, and make way for thousands of undocumented residents to purchase a health plan.

Lara first introduced his bill at the beginning of 2014 but the committee wanted a funding plan so the legislation was postponed.

“Gov. Jerry Brown said he supports the bill but California had no money to go ahead with the project,” Lara said at the conference.

Lara said he is working with immigration advocates and other organizations to find the best funding plan for the legislation, which he plans to reintroduce by early next year. Possible ideas for a funding plan include a fee for undocumented people when issuing their driver’s licenses or when they send remittances to their countries. Under the legislation, Lara said he expects at least 30 percent of undocumented people without health coverage to be able to pay for an affordable health plan.

The proposed legislation could open up a dire need for a community in the shadows, but concerns remain. Those that are undocumented or that are in mixed-status families — those with undocumented and U.S. citizen members have many fears and questions when it comes to confidentiality. These immigrants may be fearful about their own immigration status becoming known by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE).

The 2013 UCLA study said that approximately 82 percent of children of undocumented immigrants were in a mixed-status family and that 8.4 percent of citizen-children with undocumented parents were uninsured in 2007. Undocumented people may not qualify for the ACA, but U.S. citizen children or relatives still qualify. Those with permanent residency can also qualify after they’ve been in the country for five years. But some undocumented parents worry that by sharing personal information with health insurance companies for children or relatives who may have legal presence, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement could still become aware of their own immigration status.

In other cases, undocumented parents of citizen-children mistakenly believe their children don’t qualify. A study conducted in 2007 by California Health Interview Service (CHIS) estimated that 40,000 citizen-children who were uninsured and whose parents were undocumented were going to be excluded from the ACA, given the misunderstanding that children are not eligible due to parents’ immigration status.

For undocumented residents, options are few when it comes to emergency health issues. Those that are uninsured rely on emergency rooms, community health care centers, or paying for emergency services at a private clinic. Forty percent of undocumented respondents reported receiving no health or health care information when they visited a doctor, compared with 28 percent of naturalized Latinos and 20 percent of U.S. born Latinos. A national study by Pew Hispanic Research Center also said undocumented Latinos were less likely to have a health care provider. Among the reasons for this disparity, the study suggested poor access or reduced quality of care.

Adalhi Montes, 22, can relate to such hardship, having had similar experiences as an ill undocumented youth. Montes now qualifies for some health care after being approved for DACA (Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals), a program that offers temporary protection from deportation for some undocumented youth and allows them to work in the country for two-year renewable periods.

Before qualifying for health care, Adalhi was experiencing iliotibial band syndrome, an inflammation of a band of connective tissue that runs from the hip to the shinbone. But he did not know this until after visiting a couple of community clinics. In order to know what was causing the pain, Adalhi had to spend some of the money his mother had saved for his college.

“I spent my days in pain because the doctor only prescribed pain medication,” Montes said. “I spent hours making lines early in the morning so I could get checked.”

Unfortunately, not every DACA recipient knows they qualify for Medi-Cal which could help cover the cost of an emergency visit or medical treatment. Reyna Moreno, another DACA recipient, had to rush to the emergency room after she dislocated her shoulder two months before receiving Medi-Cal. Luckily, after she qualified for Medi-Cal, they agreed to cover her expenses.

Adalhi and Reyna Moreno were part of the estimated 50 percent of uninsured and undocumented youth that were ineligible for state-funded Medi-Cal back in 2007. Today, in the state of California, DACA recipients are now eligible for Medi-Cal, after California’s expansion of the program under the ACA.

On the other hand, there remain DACA recipients who don’t know they qualify. There have also been reports of social workers in Los Angeles counties that have mistakenly denied benefits such as Medi-Cal to them, according to testimonies collected by New America Media. Some social workers still aren’t aware that DACA recipients are eligible.

For local governments like California this is the time to take action on resolving the problem of providing healthcare services to undocumented communities. Especially, after the White House has announced that President Obama will delay acting on his own on immigration reform until after the midterm vote in November.

White House Officials said the goal is to shape a new immigration policy “that is sustainable,” before the end of 2014. But immigration advocates like Cristina Jimenez, co-founder and managing director of United We Dream says that this is another promise that has been broken by the President.

California needs to move ahead with its own initiatives to help resolve this humanitarian issue which is also a way to manage healthcare costs.

Meanwhile, in California for DACA recipients like Adalhi, having access to Medi-Cal has been a relief after spending a year in pain, accompanied by inadequate medical care.

“After I qualified for Medi-Cal, within a few months and with the right treatment I was able to recover my health,” he said.

Tags: DACA dreamers immigration inmigracion Latinos Salud