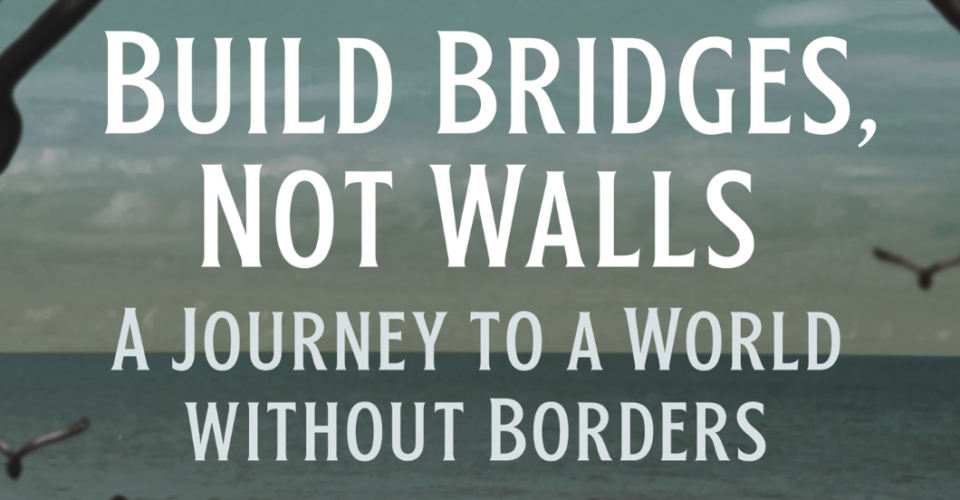

Todd Miller’s new book allows us to land more openly on its abolitionist conclusion.

By ORLANDO MAYORQUIN

EL NUEVO SOL

In his latest book, Build Bridges, Not Walls. A Journey to a World Without Borders (City Lights, San Francisco, 2021), Todd Miller reflects on his experiences researching and doing journalism on immigration at the U.S.-Mexico border over the last 15 years to grapple seriously with the idea of a borderless world. By revealing the largely disregarded sinister underpinnings of the border security apparatus, highlighting the heart-rending stories of migrants Miller has encountered in his work and contextualizing said migrants’ struggle as being born of the conditions created by a long history of colonialism, American subversion of democracy in Latin America and American capital’s incessant abuse of Latin American via exploitative trade policies, Miller synthesizes a vision that is clear: borders are unnatural. They have been erected to perversely deal with those who flee the problems created by the government of the land they seek to reach. From this starting point, Miller opens the door to abolition in the context of borders. He embraces the idea that the borders can fall and something new, a world truly concerned with justice can rise and render the border forever obsolete.

Overall, I’m a big fan of the book. I think it accomplishes a lot in relatively few pages. Miller brings us along through his thinking, which is enriched by years of meaningful experiences and research, allowing us to land more openly on his abolitionist conclusion. I believe the book was especially resonant because of all we have been learning in class this semester. The bit of context on the border we’ve developed in in a journalism class helped me more readily understand the concepts Miller lays out in the book, making for a smooth read.

By xiquinhosilva from Cacau – 84184-Da-Nang, CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=84025329

It’s hard to say who the book’s audience is. Miller told us he wrote the book with the audience of his previous books in mind. But I don’t quite remember exactly how he described that audience. Surely, people with an inclination for understanding the shames of the United States would gravitate toward Miller’s work exposing the ugliness that is the border “security.” So I would say the audience is largely American adults with a progressive persuasion. I would also say that Miller hopes — as I do — the audience is people who firmly hold to the notions the books seeks to disrupt, especially people in high places.

I would say the book looks at this phenomenon largely from within, simply because it is an explicit self-reflection where Miller tries to make sense of his own experiences covering the issue as an American journalist. That isn’t to say it is a straight memoir. Miller weaves together the journalism he has done on the topic to incorporate the perspective of several migrants,activists, a couple of CBP officers, influential intellectuals and even his imaginative young son.

The book is organized in three parts. Each part tackles a different idea while building on the previous part. He opens the first part with a powerful anecdote about encountering Juan Carlos, a Guatemalan migrant, asking him for assistance one day under the beating sun of the Arizona desert. This is a book, but you can consider this a sort of anecdotal lede. It’s an effective one. The first part provides an overview of the situation at the U.S.- Mexico border. He details the border security apparatus and the border industrial complex that sustains it. He also introduces ideas he picks up later in the book: the absurd law against helping keep alive migrants trekking across the desert, the idea of border sickness. The second part of the book explores the “higher law.” Miller challenges himself and the reader to respond to a higher, moral law and not the inhumane laws of a nation-state. In this case, he’s talking about the statutes that outlaw helping migrants as they face potential death in the desert. The final part of the book serves as a conclusion where Miller synthesizes everything in the book by making a call for abolition.

Miller is involved in the story because he uses his own experiences to help articulate his thinking. He, in a lot of ways, positions himself effectively as a proxy for his intended audience. One example is his intense internal deliberations on whether to help Juan Carlos would likely be the same for many in his audience: Should I risk breaking a federal law to help someone in need? Should I follow this unjust law or the higher law?

History is a hugely important part of the book. Miller does a lot of history in the book as it is totally necessary in properly laying out the context for the border. Miller, for example, discusses at several points during the book the devastating impact of the North American Free Trade Agreement on the working class and indigenous communities in Mexico. He also reaches far back into American history to discuss the concept of Manifest Destiny and the way that idea’s legacy reinforces the horrors of the border today.

Miller, ultimately, puts forth the final interpretation of meaning in the book. But it never really feels like I’m just reading one man’s interpretation. Miller does a good job of “showing his work.” He seems to credit other people and experiences with other people at basically every turn. He credits heavily Marcos and Servenio from the Zapatista movement for helping crystallize a vision for a more just world. He quotes writers to nicely summarize a lot of the main ideas. One of the more powerful examples of this is when he quotes Suketu Mehta’s grandfather saying “We are here because you were there.”

Tags: book Building Bridges Not Walls Todd Miller