As the number of migrant children increases, the resources for them to learn English in public schools stay stagnant.

BY RAYCHEL STEWART

EL NUEVO SOL

A five-year-old girl packs up her life as her childhood begins and follows her parents, along with two younger siblings, to a new country where she does not know the people or the language.

This was the reality for Maria, now 56.

Maria, who wishes to keep her last name private due to criticism of her employer, lived the life of a migrating child who had to learn a new language, and new way of life, at a very young age.

Originally from Tapalpa, Jalisco, Mexico, Maria left her home to travel north with her family. Once they reached the United States, the family settled in El Centro, California, just a short drive from the U.S.-Mexico border.

“Learning English was so hard, and I was at that age where they say learning a language is the easiest,” said Maria. “Having to move away to a new place, start a new school where I couldn’t talk to anyone and learn a complicated language was a lot, especially for a five-year-old!”

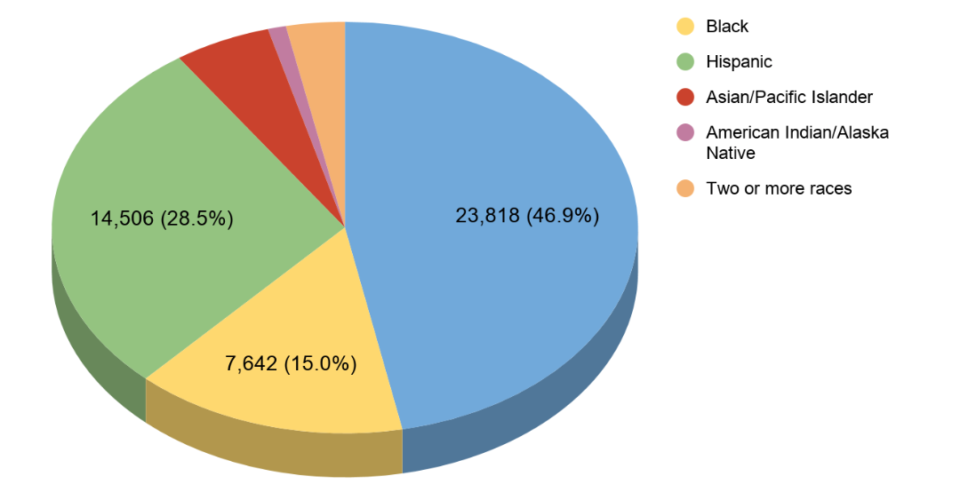

Today, public schools have taken on a new demographic compared to when Maria was in elementary school. A majority of students come from Latino, African-American and Asian backgrounds, surpassing the population of white students across the country.

When Maria was in school, it was the opposite. In 1980, the number of migrant students across the country totaled only 7%, according to U.S. census data.

“I was one of the only brown people,” said Maria. “There weren’t even any blacks, just me and a bunch of white people.”

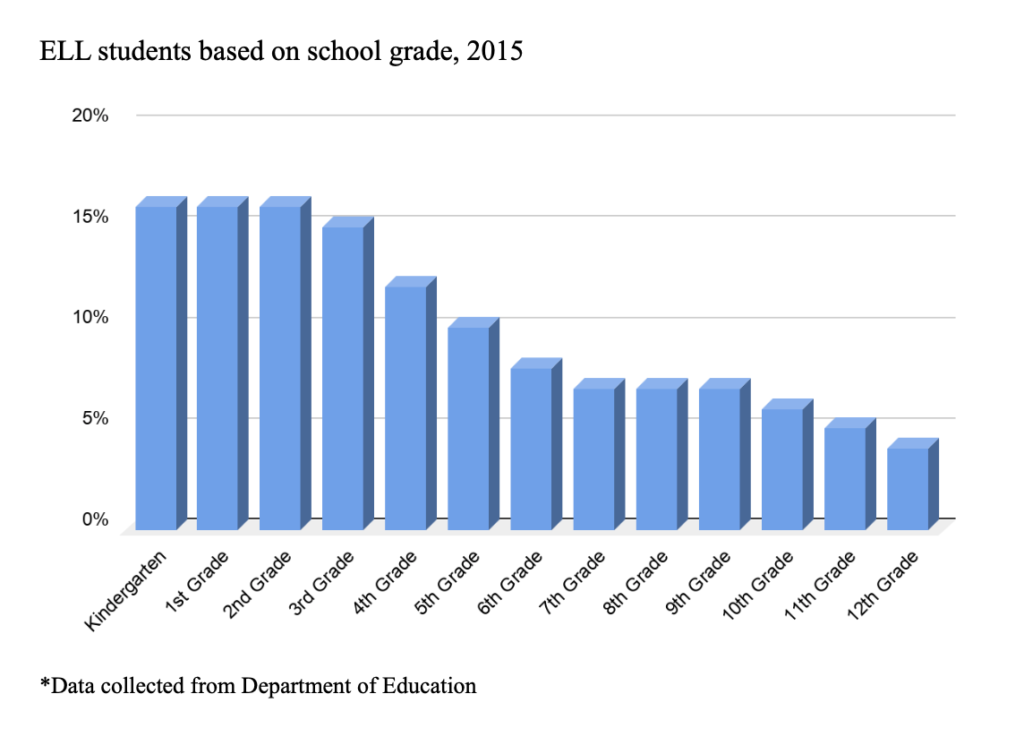

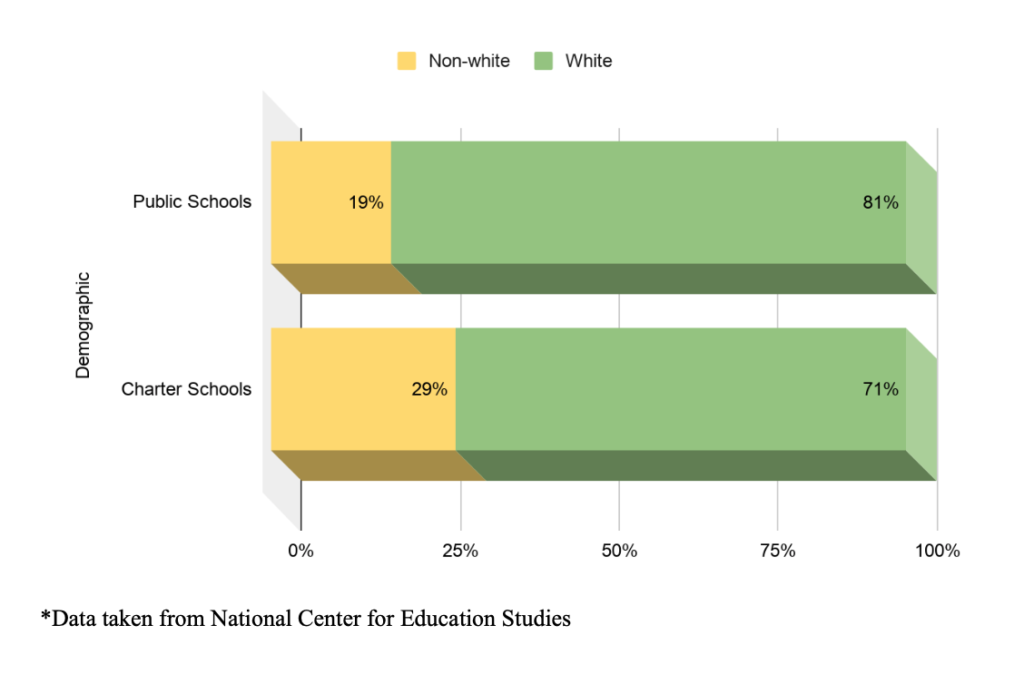

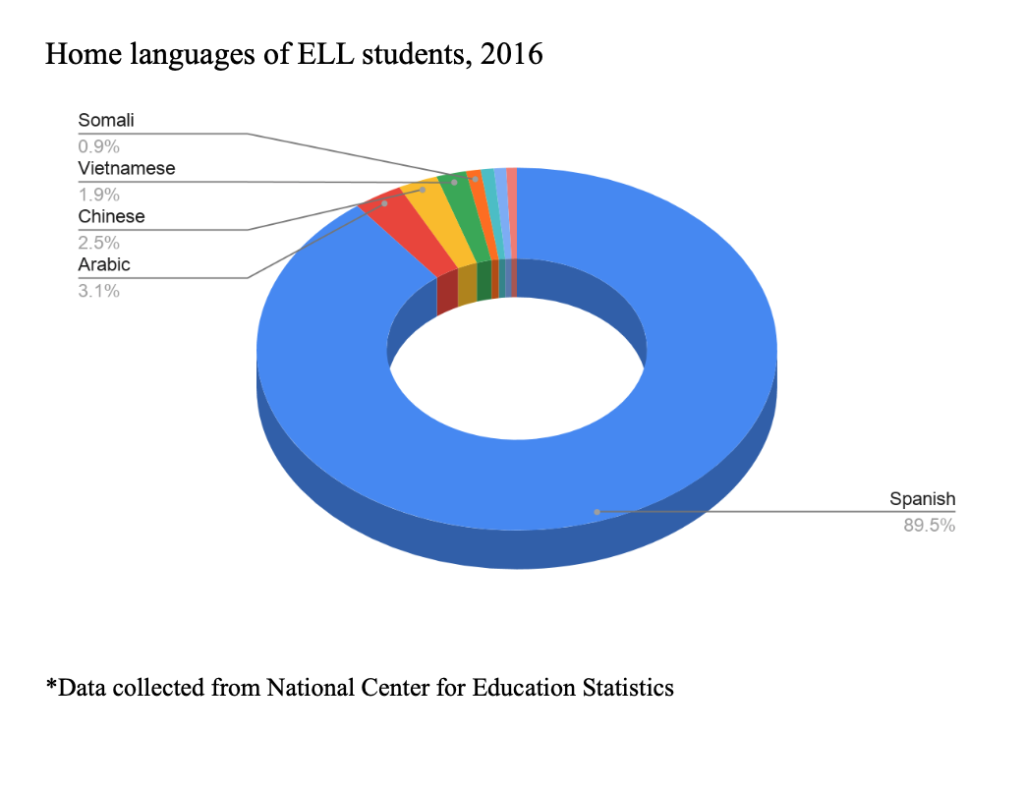

Projections show that this rate of non-white students will continue to grow, according to the National Center for Education Studies. The shift in demographics has caused a need for second-language educators to help non-English-speaking students learn the language while keeping on track with the rest of their schoolwork.

“Not only did I have to learn English, but I also had to help my siblings learn it too,” Maria said. “And I had to do all my other schoolwork. Plus, we didn’t speak English in my house so I only got practice when I was at school.”

The demographics of educators today don’t reflect the changing demographics of students in kindergarten to high school. In the 2015-16 school year, only 20% of elementary and secondary teachers were non-white, according to the Pew Research and NCES.

This lack of racially-diverse educators can greatly impair an English-learning student’s ability to learn the language while developing an understanding of their own heritage.

“All my teachers were white and didn’t really know Spanish, so they didn’t help much. It was the one ESL teacher who really helped me understand the language and how to adapt to living in this country,” said Maria.

As the number of ESL students rise, Maria, who is now a substitute teacher at an elementary school, said schools are not doing enough to keep up with the growing number, and that can inhibit a child’s chances of continuing school and even going into college.

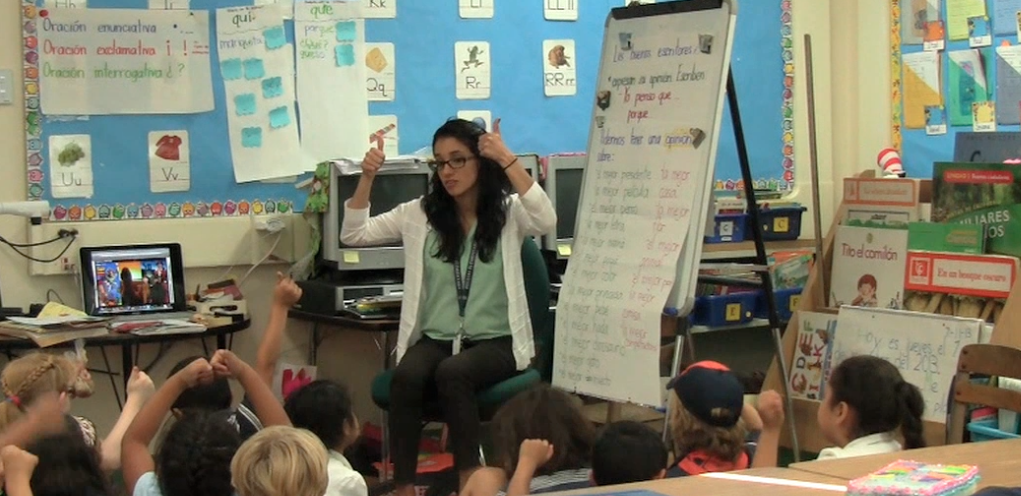

“Since I was one of the only Spanish-speakers at my elementary school, it was easy for the teacher to focus on my needs,” said Maria. “But today, when I go sub for a class there’s at least a few kids who need more help in learning English, and I’m one of the only ones who speak Spanish! So I’m the only one that can communicate with them and help them.”

When asked what can be done to help aid ESL students, Maria said more teachers who can speak the native language, and also help children embrace their ethnicity.

“Going home and going to school were like two different worlds for me. My home was Spanish-speaking and full of decorations from Mexico. The school was all American. We only spoke English and since I had an accent, I was never comfortable talking to others,” Maria said.

Natasha Kumar, Associate Professor of Education at Harvard said teachers struggle with ESL students as well. “Teachers in new immigrant destinations often find themselves dealing with a host of unexpected issues: immigrant students’ unique socio-emotional needs, community conflict, a wider range of skills in English, lack of a common language for communication with parents, and more,” she said in a research study done by Harvard’s School of Education.

Maria knew from a young age she wanted to be an elementary school teacher. She described the joy of working with kids and watching their faces light up when they learn something new.

“The kids that don’t know English don’t have that glow,” said Maria. “We live in such a diverse country, why can’t schools keep up with the diversity? All they need to do is hire people who can help these students. They’re this country’s future, we need to be helping them better themselves.”

Tags: Bilingual Education ELL ESL National Center for Education Studies Raychel Stewart