Del Bosque, alongside other active journalists, does not stop at the river. The U.S. is making the demand for the drugs, the demand for human trafficking, for laundering the money. A lot of that happens here and it’s all one system, and someone has to write about it.

Melissa Del Bosque, reporter for the Texas Observer, is dedicated to covering the border and all that comes with it, keeping an eye out on current events via her blog La Línea. Photo: Dalia Andrade/El Nuevo Sol

By ALEJANDRA VÁSQUEZ

EL NUEVO SOL

Listen to Melissa del Bosque’s presentation at CSUN vía KPFK:

[audio:http://archive.kpfk.org/mp3/kpfk_140310_203030indymed.MP3]

“The people who tell the stories are usually the people who win or the powerful ones, but there’s always people who are not powerful and don’t have a voice,” said Melissa Del Bosque, a reporter for the Texas Observer covering the El Paso – Juarez border.

CSUN had the honor of having this reporter share with journalism students, professors and other spectators, some of her experiences and cruel stories that are happening every day in the Mexico-U.S. border.

In recent years, many reporters are being known for writing about drug cartels and the physical violence that drug trafficking brings with it. It is a difficult task to have the courage to write about the economic violence from which the Mexican border and its people have been victims of.

Del Bosque, has been devoting her work to create awareness on the injustice, brutality and violence that is happening in the Mexico-U.S. borders of the states of Chihuahua, Coahuila, Nuevo Leon and Tamaulipas.

Tamaulipas is the state where she has been a witness of her most controversial stories.

The Movimiento por la Paz con Justicia y Dignidad reported in 2012 that since the conflict began in 2006 with Felipe Calderon’s presidency, there were an estimated report of 80,000 deaths, 20,000 people disappeared and 250,000 people displaced. These numbers are constantly changing.

Del Bosque says that one of the most difficult aspects that come with writing about this conflict is the ability to obtain reliable information on what is actually happening. The problem is that many people don’t report killings and disappearances and authorities refuse to investigate a lot of them.

Writing about violence was never planned for this reporter, “I didn’t choose the stories, they chose me,” said Del Bosque when she began narrating how she decided to write about the organized crime that exists in the Aztec land.

It all began when she decided to go to Reynosa, the capital of Tamaulipas, and write about the unaccompanied children that are detained by the U.S. border officers when trying to cross to “el otro lado” (the other side). These minors are usually, repatriated to Mexico, when many of them are originally from Central America.

There was an intense environment the first time she visited; a grenade had just hit the mayor’s office and federal officers and armies circulated in their trucks with high caliber rifles on the empty streets.

She was there for two weeks, visiting the state shelters every day, and being there with the children allowed her to learn that after they were deported by border patrol, these kids were being recruited and kidnapped by the cartels. “I talked to two brothers who watched their mother die in the desert after they had crossed the river and then they had to deal with this insecure crises, on top of everything else,” said Del Bosque.

Hoping to interview kids from Central America, she spoke to a reporter who she knew from several years back. “He told me, ‘I can help you I know where they are, but I have to ask the cartel first,’” narrated Del Bosque, who later understood the need for this. It was common for the cartel informants to know who would come and leave the city, because in order to gain access, you would have to go through their checkpoints, but they would also control the information being published.

“Not only did they say, ‘no, you can’t publish the story,’ but they also threatened to kill him if they caught him helping me.” Del Bosque saw no other solution than to quit the story.

According to an article published last year by the Reporteros sin Fronteras por la Libertad de Información, in the last decade 80 journalists have been killed, 17 disappeared and different media outlets are frequent targets of attacks and threats.

Another violent situation that continues generating more deaths in the Mexican border occurs in a small town in Guadalupe, Tamaulipas, where the people who are believed to be protecting the citizens are burning down innocent people’s homes.

This is what has begun to be known as “authorized crime,” a structure of organized crime and political system where crimes are allowed to happen. Especially to innocent people, said Del Bosque, where the majority of the victims are activists, reporters, human rights defenders and anyone who would raise awareness on the injustices and violence that targets innocent people.

Contrary to what many would think of Mexico as not being a profitable country, Del Bosque added that the country’s natural resources can’t be developed as a result of this economic violence. People from Tamaulipas and Chihuahua who are landowners are targeted by the organized crime.

She said it is very common to be kidnapped and be bereft from your land titles. “People from a town told me they owned land along the river, who were threaded off of their land, and their land was taken from them.” This doesn’t look well on the future of the country said Del Bosque, when more and more communities see themselves experiencing this authorized crime.

Due to the negligence of the U.S. media in accurately covering the violence at the border, Del Bosque criticized the idea of not making public the cruel reality that is happening in this area, arguing that there could be an invested interest from both sides of the border.

“It’s kind of like a dysfunctional family where one of the family members has issues but nobody talks about it, because it raises all sorts of different questions,” said Del Bosque.

Del Bosque claims that this is due to a “sophisticated publicity campaign” that is backed by the Mexican government. She talked about the recent Time cover story about Mexican President, Enrique Peña Nieto, noting that the author who wrote the story wrote it in Washington D.C.

“Have you talked to anyone in Mexico before writing the story?

This could be the reason, she continued, of why there’s a lot more coverage and criticism in what is happening in Venezuela and not on what is happening on our neighboring side. Criticizing the Venezuelan government is more politically beneficial than criticizing the Mexican government because there’s too much business and political interest at risk.

Rosa Moreno, a single mother of six, is one of the many women who worked for the foreign owned maquiladoras in the Mexican, borderland territory. She worked for two months for the South Korean firm, LG electronics, a maquiladora that produces flat screens for televisions. On February 19, 2011, Moreno was working with a 200-ton press that malfunctioned and smashed both of her hands. She was taken to a regular clinic in order to avoid any government report, where they had to amputate both of her hands. She was offered $3,800 in settlement.

Del Bosque decided to write Moreno’s story because she considered it important to let people know and understand the lives of the people who work under the corrupt system. “It’s good to have jobs, but that job has to pay you enough to be able to have a dignified life style.”

Working in politics for five years allowed her to understand how laws were made and how they really impact people’s lives and sometimes they are even made not for the best reason.

People have to understand that these things can be changed. That this was done by a body of legislators that decided to pay them a low wage, to hire them on a temporary contract – as Rosa and many other maquiladora workers are – and work under terrible conditions. These policies could be changed, but first people have to be aware of the corruption and be willing to do something in order to change these situations.

Del Bosque is looking to work on stories about the violence and the organized crime that is happening on this side of the border. We hear a lot about Mexican reporters, but as Del Bosque mentioned, “it doesn’t stop at the river.”

Del Bosque, alongside other active journalists, does not stop at the river. The U.S. is making the demand for the drugs, the demand for human trafficking, for laundering the money. A lot of that happens here and it’s all one system, and someone has to write about it.

Related Articles

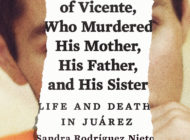

A deadly promise: Human rights activists flee Juárez

University librarian keeps tally of the murders in Juárez, México

More than words: Photojournalist captures the violence in México

Tags: Alejandra Vázquez border Ciudad Juárez frontera Juarez Melissa del Bosque